New

Evidence on the Lewis and Clark Air Rifle – an “Assault Rifle” of 1803.

Keywords:

Lewis and Clark, Meriwether Lewis, William Clark, Lewis and Clark Air Rifle, Lukens,

Beeman Girandoni, Girardoni, Gilardoni, Girandony, G, Air Gun, Airgun, Military, Repeater,

Repeating, Rodney, Expedition, Sioux, Brunot Island, Voyage of Discovery, Corps of

Discovery, Cowan, Keller, Carrick, Currie, Baker,

Baer, Hummelberger,

Eichstädt, Stewart.

By Robert D.

Beeman Ph.D.[1]

Based on the author's research and publications since 1976 and our Lewis and Clark website established here 23 March 1999. Basic new discoveries announced on this website on 19 March 2005. Latest update of this chapter 15 May 2008.

For additional information on the Lewis Airgun, related guns, and the reproduction of these guns, click on the Austrian Large Bore Airguns and the We Proceeded On to the Lewis Airgun III sections of this website.

SEE the notice about the surprising donation of the Beeman/Girandoni airgun at the end of this section! And see the note near the end about what publications around the world have been saying about the Beeman/Girandoni airgun!

INTRODUCTION

As elaborated in the previous chapter, the search for the air

rifle carried by Meriwether Lewis in 1803-06 seems to have been started over 50 years ago by Charter Harrison (Harrison, 1956a, 1956b, 1957), America’s

first major airgun collector. That was followed by Roy Chatters (1973, 1977) and

Henry Stewart Jr. (1977, 1982). As also noted, a meeting in Stewart’s gun room

in January 1976 inspired the author to continue the search for the next 32+

years. After Stewart's last comments on the matter in 1982, Mrs. Beeman

and I continued that search and study virtually alone for the next 20 years, producing several publications

(Beeman 1977, 1999, 2000, 2002a, 2002b, 2004a, 2004b, 2005a, 2005b, 2006) and,

for many years, posting a large Lewis and Clark Airgun section on our

website (www.Beemans.net). By sheer coincidence, our acquisition of

a Girandoni air rifle, Girandoni air pistol, and several Girandoni-system

airguns in the 1970s also ignited a passion for the Girandoni-system airguns and

we studied and collected them, along with many other antique airguns, around the

world for over three decades.

In 2002, Mike Carrick brought attention to a tiny passage in Smith and Swick’s

recent (1997) transcription of an 1803 travel diary of one Thomas Rodney which

described Lewis handling a gun which, according to his description, obviously was a Girandoni-system airgun.

After a brief period of acceptance of this idea, I, and many other Girandoni and

Lewis and Clark students, came to feel that an astute person would find it much

more logical to reject Rodney’s report as spurious (Beeman, 2004). Based on the

best information known at that time, including many details and images from the

outstanding work by the British Girandoni students, Colin Curie and Geoffrey

Baker (2002), I used our specimen of a Girandoni military repeating air rifle to

illustrate our repudiation of the idea of Lewis’ airgun being a Girandoni

(Beeman 2002 website and Beeman Mss., 2003 -published 2004).If the above series were compared to telling the story of the WW2

Pacific Campaign then, after considering many great battles, we would finally

come to the discovery and use of the atomic bomb.

The bombshell in this present series was a startling series of discoveries, during November 2003 to March 2005 by Ernest Cowan and Richard Keller in their shop in Chambersburg, Pennsylvania. Finally, after over two hundred years, Cowan and Keller claimed that they have found the Lewis airgun and, after severe consideration, that conclusion has become the core of a consensus of Ernest Cowan, Richard Keller, Colin Currie, Geoffrey Baker, myself, and a wide group of other arms experts. Telling more in this introduction would slight the significance and details of the discovery and the consensus, due to lack of perspective, and it would detract from what I hope will be the reader’s enjoyment of engaging in our “mystery” approach which reveals these amazing new findings, clue by clue, and explains and expands our considerations of each point. The new evidence about the Lewis airgun adds a late, but dramatic and revolutionary, twist to the decades long story of this gun.

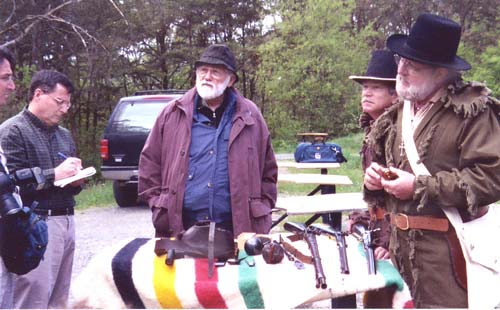

The latest developments in the Lewis Airgun story were first publicly announced by Ernest Cowan, Richard Keller, and Robert Beeman at the famous Baltimore Antique Arms Show on March 19-20, 2005. The distinguished judging panel of that show awarded the Beemans the “Best Gun of Show” award for the Beeman Girandoni. The show's “Best Exhibit” award was presented to Cowan and Keller for their superb presentation of the Lewis and Clark airgun, and the Lewis and Clark "Short Rifle" firearm. The airgun findings were presented to international view on March 19, 2005 by being added to the Lewis Airgun sections which had been running for many years on the www.Beemans.net website. Announcement (Beeman, 2006) of the apparent discovery of the Lewis airgun and the apparent identification of the Lewis and Clark short rifle (Cowan and Keller, 2006) were both published in the May 2006 issue of We Proceeded On, the official publication of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Association . The new information also has personally been presented to gun collecting clubs and other interested groups in the northeast USA by Ernest Cowan and Richard Keller, and to a far lesser degree, by National Firearms Museum Curator Phillip Schreier and the author.

The first three of the above sources largely have been the bases for several articles, including Saunders (2006), Schreier (2006), Eichstädt (2007), and Beeman (2007), which have popularized these latest airgun discoveries and their significances. These short reports were extremely condensed and some were heavily edited by the publishers. It was inevitable that some details would be slighted or even incorrectly printed, but most important, credit for the various discoveries, diagrams, images, and ideas was sometimes slighted, deleted, or even worse, incorrectly credited. I may not be the key person in these presentations, but having the large responsibility of being the long term “teller-of-the-tale” I surely want to be the one who sees that proper credit is placed where it is due. So, to get the proper information on this latest chapter, read on – remembering that the real hero of the story is Lewis’ airgun and that without the present specimen, this new chapter would not exist! For even more detailed information, illustrations, and credits, see the other chapters of this presentation and the books on the Lewis airgun and Girandoni airguns now in preparation by the author.

The long search for the air rifle carried on the Lewis and Clark Expedition has taken an amazing turn!

Thus the five decade search for the Lewis airgun has a new chapter. New study of an actual Girandoni military repeating air rifle and continuing study, here in America by Ernst Cowan and Rick Keller, supplemented overseas by Colin Currie and Geoffrey Baker, plus further international study by Beeman, of the Girandoni system and related historical documents apparently has removed all of the objections to Carrick's claim (2002, 2003) that such a rifle was carried by Captains Meriwether Lewis and William Clark on their exploration trip to the Pacific Northwest during the years 1803 to 1806 and to Cowan and Keller's claim that they have identified the actual specimen.

This elusive arm was mentioned 39 times in the expedition journals (Moulton, 1986-2001), more than any other weapon on the trip, but was never described. It seemed to have disappeared in the last weeks of 1806 when it was sent in Box No. 2 of two boxes to be taken from St. Louis by a Lt. Peters[2]. The last direct record of it was found in a notice in the Franklin Institute of Philadelphia of the auction of the Isaiah Lukens estate on 4 January 1847. Item #95 was “1 large air gun made for and used by Messrs. Lewis and Clark in their exploring expeditions”. It was withdrawn from public sale at that auction. Almost surely, it went into the unheralded holdings of a private family, rather than a formal gun collection, and was handed down through four or five generations to the 20th century.

Lewis committed suicide in 1809, before rendering any of the expedition journals. The actual journals of Lewis and Clark didn't get published until 1904-06, and then incompletely. The complete journals did not appear in print until 2001 (Moulton, 1986-2001). Apparently the only 19th century references to the Lewis and Clark airgun appeared within Biddle's 1814 paraphrasing of the journals - which only made four mentions of the airgun and gave no details. Biddle's writings were very poorly distributed and almost unknown, even at the time. So while the historical spark, and general opening of perspective, created by the success of the expedition may have had immense ramifications, there virtually was no public awareness of the expedition's airgun.

For over 100 years there seemed to be no sign of the gun. Having already made it through the expedition, the terrible destructions in America of the War of 1812, and 41 years past the expedition, it would be quite unlikely that it was destroyed later. We would certainly expect that such a beautifully made, most unusual gun would be carefully maintained, even though its historical significance probably would not have been appreciated. (Remember that the adulation of Lewis and Clark did not become strong until well into the 20th century.) Surely, it must still exist, among extremely few potential candidates, somewhere in the United States, most likely in one of the very few American collections which contain such guns.

Speculation from 1956 (Harrison, 1956a-b, 1957, Chatters (1973, 1977)) to 1982 (Stewart, 1977, 1982) pointed to various specimens. Intense research in the years 1977 to 2004 (Beeman, 1977, 1999, 2000, 2002a, 2002b, 2004a, 2004b) led most historians to accept that the airgun of the expedition was a .32 caliber muzzle-loading air rifle made by Seneca and/or Isaiah Lukens of the Philadelphia gunmaking area.

N.B. The reader who is not very familiar with the very unusual Girandoni air rifle system might find the following sections much easier to follow if he would first skip ahead to the last part of the article where newly corrected information on the Girandoni air rifle and its functioning are discussed and illustrated in detail.

A Description of the Lewis Airgun Emerges!

The recent publication (Smith and Swick, 1997) of a little known travel diary journal of a Thomas Rodney, who was a day visitor to Captain Meriwether Lewis while he was traveling down the Ohio River at Wheeling, Ohio in September of 1803, contains a tiny passage which has caused new thinking about the Lewis airgun. The passage reads:

Visited Captain Lewess barge. He shewed us his air gun which fired 22 times at one charge. He shewed us the mode of charging her and then loaded with 12 balls which he intended to fire one at a time; but she by some means lost the whole charge of air at the first fire. He charged her again and then she fired twice. He then found the cause and in some measure prevented the airs escaping, and then she fired seven times; but when in perfect order she fires 22 times in a minute. All the balls are put at once into a short side barrel and are then droped into the chamber of the gun one at a time by moving a spring; and when the triger is pulled just so much air escapes out of the air bag which forms the britch of the gun as serves for one ball. It is a curious peice of workmanship not easily discribed and therefore I omit attempting it.”

Any airgun historian or student would immediately realize that this description could only apply to a Girandoni system repeating air rifle. Michael Carrick (2002, 2003), an outstanding Lewis and Clark and arms historian, did the Lewis and Clark "fraternity" and students of antique arms an immense service when he brought Smith and Swick's1997 book, which was widely circulated but appeared to be of little interest to Lewis and Clark or arms historians, to their attention. While there is no doubt that Rodney's report described a Girandoni-system airgun, that report in itself does not prove that Lewis' airgun was a Girandoni system airgun.

.

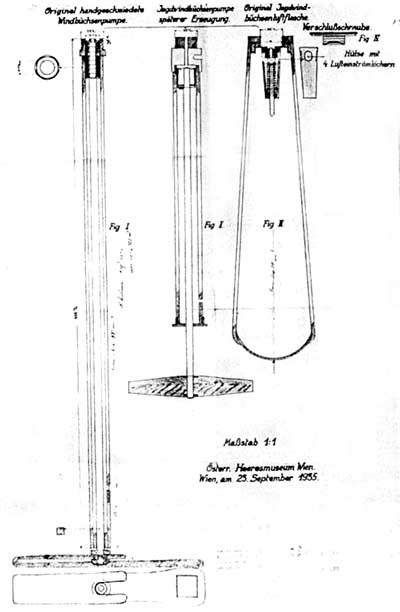

Figure 1. Girandoni military model repeating air rifle invented by Bartholomäus Girandoni, Vienna, Model of 1780. Full length view, right hand side. Breech loading, rapid fire repeater, issued with two extra air reservoirs and three extra 20 shot speed loading tubes. At first, a long hand pump was provided to every soldier, later to every other soldier. The magazine has always been described as holding 20 balls, but this specimen has a capacity, with one ball in the firing position, of 22 balls. Note that the air reservoir serves as the buttstock and does indeed look “bag shaped”, consistent with Rodney’s remark (Smith and Swick, 1997) about the ” air bag which forms the britch (breech) of the gun”. (The Girandoni photos of this chapter illustrate the "Beeman Girandoni" - from the Beeman Airgun Collection. All photos of Beeman collection by Robert Beeman; reproduction forbidden without written permission of Robert Beeman.) ©2002, Robert David Beeman

Fig 2. . Beeman Girandoni - showing tubular ball magazine on right side of gun, distinctive loading block traversing the receiver. Note that receiver casting is a single, seamless top piece. Beeman collection. ©2002, Robert David Beeman

Carrick accepted the Rodney report as revealing that Lewis probably carried a Girandoni-system airgun. At first there was a burst of acceptance of the Rodney report, but upon some reflection, I, and most airgun historians and experts, began to have severe doubts that this report could be correct. It would seem that Carrick, and others, made a huge, understandable, but rather elitist, assumption by pointing to Rodney’s character and position as supporting his credibility. The present author, and many others, felt that, looking at the credibility-related remarks repeatedly stated by Rodney’s editors, the records of the expedition, and especially considering what we then thought we knew about Girandoni airguns, and that no repeating airgun which bore evidence of being the Lewis airgun appeared to exist, Rodney’s credibility should be questioned and that this paragraph of his report could be spurious (Beeman, 2004).

The editors of Rodney’s journal warned readers that Rodney, despite being a judge and a noted politician, indeed on an appointment from Thomas Jefferson, had had a “bumpy career” including multiple accusations of corruption, bribery, and theft of funds which had led to prison time. Especially strong was the remark by his own editors: “Assuredly, both creative exaggeration and rich embellishment had their share in coloring his memory – it is impossible to sift fact from fancy in some of his descriptions”. While Smith and Swick seem enthralled with this most unusual man, a careful reading of their introduction reveals that the effusive, enthusiastic, mystic Thomas Rodney must have been an odd duck and a rascal with the morality of an unrepentant politician combined with a driven ability to prolifically write in a self-aggrandizing manner. This feeling is reinforced as one reads the entire book, but, as I noted in my previous papers, of those tales of Rodney which are now considered fanciful, most were directed at increasing his own significance in history.

Objections to a Girandoni as the Lewis and Clark Airgun:

The above description depicts a gun which should have been a real star item on a wilderness expedition. Outside of the obvious basic problem that no known specimen of airgun seemed to fit the Rodney account, what objections were raised to the proposal that the Lewis and Clark air rifle was a Girandoni-system airgun?

To condense the key objections, based on our previous knowledge of the Girandoni (Beeman, 2004):

Standing alone, the Rodney report was not fully compelling and contained large seeds of doubt. There seemed to be more reasons NOT to believe it than to accept it. Many Lewis and Clark and airgun history students remained supportive of the Lukens DNH .32" caliber air rifle as the Lewis airgun. It has now become clear that if Rodney's passage about the airgun has credibility, that rests, not on Rodney’s character or social position, but on three very special things: 1) The number 22. The Girandoni military air rifles basically were designed as 20-shot guns, with 20-shot speed loaders, etc. Certainly all accounts about the gun which could have reached Rodney would have given 20 as the shot count of the gun. Even today, all previous references gave 20 balls as the capacity of the gun. But 22 is the correct ball capacity of the Girandoni military air rifle. 2) The phrasing of his report. The ways that he describes leakage, firing failure, etc. are not the kinds of phrases that one would conjure up to inject impressive details into a contrived tale. 3) We now have an actual specimen of a repeating airgun which supports each previously suspect detail of the narratives.

The Turning Point:

The turning point in this study came as the accidental result of a most unlikely series of events. Ernest Cowan and Richard Keller, the highly respected, master museum-copy gun maker/historians who are known for their incredible, high-end museum-copies of the Ferguson multi-thread breech loading flintlock and other antique guns, became interested in making a set of just four precision, authentic museum-copies[14] of a Girandoni repeating air rifle. This desire stemmed from the fact that these two gentlemen were among those who were convinced by Carrick's conclusion that the Rodney paper was a legitimate report of Lewis' airgun as a Girandoni system arm. The Beeman paper (2004) gave strong evidence that such a conclusion was not yet justified at that time.

Their first step was to locate a Girandoni air rifle that they could use to precisely guide their work, but no such specimen was immediately evident in America. Cowan contacted the outstanding British gun illustration experts Geoffrey Baker and Colin Currie, who had just published a preliminary set of working diagrams of the Girandoni Austrian Military Air Rifle (Baker and Currie, 2002). They referred him to the Beeman Airgun Collection in California as having America's best collection of Girandoni and Girandoni-system airguns, including the only specimen known in America of the Girandoni military repeating air rifle. So Cowan called to ask if they could borrow our military Girandoni repeater and completely disassemble and study it. In early November 2003 we consented to such an exhaustive study of the "crown jewel" of our collection. This step triggered the following most unexpected and amazing series of events:

SIX AREAS OF NEW EVIDENCE ABOUT THE IDENTITY OF THE LEWIS AIRGUN

Evidence Area 1: The Replaced Mainspring

After many months of intense confidential study of the "Beeman Girandoni", Cowan and Keller concluded that this gun definitely is an authentic military version made in the Girandoni shop. Baker and Currie, studying Girandoni design and function in England, concurred with this conclusion. While studying details of the special flat mainspring, Cowan made a startling, most unexpected discovery: the mainspring is a replacement! And, our mainspring was not just a replacement, but a very old replacement that apparently had been made using a farrier’s file (a horse hoof trimming file - a type of coarse rasp also commonly used as a rough wood rasp) as spring material. A small area under the mainspring revealed the almost completely removed diamond shaped groove pattern of such a double cut file. Other astonishing discoveries about this gun were made in the Cowan shop before it went into high security storage at the U.S. Army War College in March 2005. (In March 2006 it was moved to a Lewis and Clark display at NRA's National Firearms Museum. In May 2007 it went to its final home at the Army War College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania - but that is getting ahead of our story.)

Figure 3. Inside view of the Beeman Girandoni military air rifle lock with hammer in the resting position. The heavy flat mainspring extends along the forward two thirds of the lock plate. This unusually strong mainspring allowed much greater stored air pressure than the traditional V shaped spring (thus allowing the potentially higher power of the Girandoni design.) Beeman collection. ©2002, Robert David Beeman

Fig. 4. Underside of the flat mainspring as removed from the Beeman Girandoni (“the study rifle”) by Ernie Cowan. Cowan noted that this replacement spring apparently was made from a farrier’s file as evidenced by the diamond pattern in the forward region. Above is a slightly different farrier’s file that has been ground down by Cowan to show the distinctive diamond shaped marks. Just a few more strokes of the spring maker’s file and these marks would have been gone, but a few more strokes and the spring might have been too thin. (Unless otherwise noted, scales in my images are marked in millimeters.) Beeman collection and photo. ©2005, Robert David Beeman

Lewis had recorded on June 9, 1805 (probably June 10, 1805) that the mainspring on his airgun was repaired[16].He wrote that "Shields renewed the main Spring of my air gun we have been much indebted to the ingenuity of this man on many occasions, without having served any regular apprenticeship to any trade, he makes his own tools principally and works extremely well in either wood or metal..." That Lewis's airgun had a replaced mainspring is one of the only solid bits of evidence that the expedition journals reveal about his airgun. Such a repair to this gun is of the very kind that would be expected of John Shields, the expedition’s well-experienced, much praised gunsmith/blacksmith[15]. A farrier's file probably would have been the only piece of suitable metal and size that would have been available to replace such a long, thick mainspring in a wilderness setting. It is possible that such a file would have been even better material for this purpose than the original, early type of steels used by Girandoni. Lewis made it clear, in the above note and elsewhere, that Shields was capable of such special work as shaping, annealing, and re-tempering the file metal. A farrier's file would be expected among the large amount of equipment and supplies carried by the expedition's gunsmith/blacksmiths. It would have been a basic item for rough repairs of the many heavy wood items as well as for caring for the horses that the expedition expected to obtain in the Rockies. We certainly would not expect a gunsmith in a civilized area to utilize such an odd source of material.

Many modern readers, especially Europeans, might not feel that a blacksmith would be suitable as a gunsmith. In Europe the frontier has been gone for centuries and the crafts became rigidly separated by guild rules. Some Europeans have a hard time thinking of blacksmiths, which in Europe generally were heavy-handed, rough workers, as doing gunsmith work. However, on the sparsely populated frontiers of early America it was common to combine the roles of blacksmith, gunsmith, farrier, and even handyman. The forge of an American blacksmith was ideal, not only for making wagon or boat parts and horseshoes, but also for annealing and tempering gun springs. Such workers could fix a rifle lock as well as hammer out a rudder strap or shoe a horse. Shields evidently was an especially skilled and talented example of such a craftsman.

A broken mainspring would not be expected in a Girandoni system gun with the correct flat mainspring[17]. The design and great ruggedness of this very special mainspring would be expected to avoid the breaks that almost are routine with the typical flintlock V-shaped mainsprings, with their back bend of extreme stress. In normal use, the likelihood of such a flat mainspring breaking within the closed gun should be close to nil. However, a secret Achilles heel of the big, flat Girandoni mainspring has been discovered. Careful examination of the inside view of our lockplate will reveal that the mainspring of the lock removed from our Girandoni has been restrained by a drift punch. Fortunately, I had the advantage of having read Baker and Currie’s first study of the Girandoni military air rifle before disassembling the gun. There the purpose of the mysterious little hole in the lock plate is revealed. Obviously a traditional spring clamp, designed to compress the V-shaped mainspring found in most flintlock firearms, cannot be used to restrain a flat mainspring. Placing a drift punch through this hole will allow disassembly, cleaning, and repair of the removed lock assembly without the sudden release and breakage of the flat mainspring! Unfortunately, the men of the Voyage of Discovery did not have such a manual and the mainspring easily could have been broken when taking the gun's lock apart for cleaning (or drying!). Or the original mainspring could have been made of some of the "faulty iron" that plagued Girandoni.

There is another possible cause of the mainspring breakage. Private Whitehouse recorded using the airgun to signal to a lost member of the party[18]. Martin Orro and Henry Elwood (personal communication, 15 August 2004) have shown that it is possible to fire a butt reservoir air rifle (a replica of the Lukens DNH), by snapping the external hammer/cocking lever several times in a minute, to create a distinctive and attention getting staccato. If such a practice had repeatedly been carried out it might have been injurious to the metal structure of the mainspring and possibly contributed to a failure.

The discovery of the replaced mainspring led to consideration of several other areas of evidence about this specimen:

Evidence Area 2: Number of Shots Per Air Charge

Wood and Thiessen (1985) [22] note that the narratives of Charles McKenzie, whose visit to the Hidatsa and Mandan Indians in 1804 overlapped that of Lewis and Clark. McKenzie, reported that “The Indians admired the air gun as it could discharge forty shots out of one load, but they dreaded the magic of the owners.” Of course, by "40 shots out of one load", it has always been clear to us that that meant 40 shots from one charge of air. This is how modern PCP shooters often refer to their shooting capacity, and even in the 19th century the single shot Giffard CO2 guns were promoted as "firing 300 shots from a single load". I formerly had felt that a Girandoni could not hold enough air to fire forty of those huge lead balls. But now, actually having fired 64+ balls on a single air charge, that no longer is a reservation. Even a smaller, a quite different, Staudenmayer butt reservoir gun gave one test run which showed a tank capacity of 39 shots. (Konwiarz, 1983). Butt reservoir guns typically can fire 35 to 50 shots per single air charge while ball reservoir guns generally can manage only 10 to 20 shots. A magazine size of 40 is unknown in any specimen. Such a tube length would be absurd; it would be clumsy and serve no particular function; loaded it would add great weight, and such a gravity fed magazine would cause ball deformation as the soft lead balls in a partially filled magazine slammed back and forth with considerable force in that very long tube as the gun's muzzle was pointed up and down. Significantly, no specimens of any Girandoni-system airguns are known with such a vastly extended magazine.

There could be several explanations of McKenzie's comment. Perhaps the most likely is the most casual - he saw it fired many, many times , an astonishing number of times, but not even to the end of a magazine load. Lewis probably never allowed that to happen - I would never have allowed the gun to run to empty in view of an Indian if I had been in Lewis' place. Stopping short of empty would give the impression, to those unfamiliar with repeaters, that "this gun can continue to fire forever!" And Lewis simply told McKenzie a basic fact about the gun - it can fire about 40 times - meaning 40 times on a single air charge. The shots beyond 20 would not be world beaters, but just firing them would have been impressive. Also, forty is exactly two speedloader loads, representing a quick and easy way to load the magazine. Lewis may have let someone, maybe just another expedition member, see him load the balls into the gun - he may well have fired a magazine load, and then a quick speedloader refill - to come to that amazing total. Original instructions to Austrian soldiers advised them to only fire one loader tube of 20 balls before switching to another fully charged air reservoir. (The partially used reservoir could be topped-off with the hand pump during a lull in battle. Evidently those hand pumps were intended only for such field topping-off operations.)

About the same time as we were considering the mainspring repair matter, the British experts Baker and Currie had been conducting test firings with a .51 caliber Girandoni replica. They got 35 shots before they got tired. If that gun had been made in the correct .46 caliber Girandoni, like this one, it would have provided an even higher shot count. So, the 40 shots per charge (load) point[19] (see Beeman, 2004) could no longer be used to rule out a Girandoni system air rifle. Now we were looking at this gun in a whole new light and even more surprises were forthcoming from this gun's examination..

The most recent tests, noted above, by the author using "G4", his Cowan-made exact museum copy of the Beeman Girandoni, revealed a most telling result: starting with an air charge of 800 psi, this gun fired 64 lead balls from a single charge of air! And even that last ball was significantly deformed when it struck a metal plate! It would seem that even that last ball could have been very harmful to a human skull!

Evidence Area 3: Damage to the Airgun

This Girandoni air rifle evidently was the victim of a major accident. On August 6, 1805, while ascending the Jefferson River, three of the canoes swamped while navigating rapids. At least one of them struck rocks and nearly crushed Private Whitehouse. There was considerable loss and much damage to equipment, which appears to have included the air rifle. In his journal entry for the next day, Captain Lewis wrote, "my air gun was out of order and her sights had been removed by some accedent I put her in order and regulated her. She shot again as well as she ever did." indicate not only that the airgun was among the damaged items but that the airgun had been in regular good use. Although the expedition airgun surely would have been wrapped in a manny cloth, or similar cover, it could have sustained severe damage by impact against stream rocks. Very close examination of the Beeman Girandoni reveals subtle signs of severe impact damage, to the center and left of the forward part of the gun, that is consistent with such an accident. Except for the front sight, the damage was not of the nature which would interfere with the practical use of the airgun. The forward barrel lug that bears a cross pin which retains the brass nose cap on the forward tip of the stock, has been torn open and later partially repaired. Sections of stock wood on each side of the loading slide have been broken out as would be expected from severe impact to the upper side of the gun. The forward end of the very thin, full-length forearm wood must have suffered extreme damage. It must have been subject to some makeshift field repair, perhaps just lashing, to hold it together. The original cast brass middle thimble evidently was crushed and an inconsistent rolled brass thimble, of American styling, substituted at the time of the field repair or later permanent repair. (The original cast part could not have been bent back into shape without breaking.) The existing wooden cleaning rod ( the “ramrod” in such an airgun is used only for cleaning and clearing the bore) clearly is a replacement; consistent with the center and left front area of the barrel and stock being severely impacted[20]. The forearm now shows an excellent repair in which the forward section of the forearm has been given a very old, but excellent, replacement. The replaced piece is expertly inletted to the contours of the underside of the barrel and very nicely joined to the original stock with a scarph joint. Scarph joints are very long angled joints used for millennia in shipbuilding to solve the problem of securely end joining long, thin pieces of wood. The scarph joint was adopted by 18th and 19th century gunsmiths to make secure end-to-end joints in the wood of long, very thin flintlock forearms[21]. Such joints virtually never were used by 20th century gunsmiths because they generally no longer had to deal with forearms with such incredibly thin wooden walls. Perhaps the most interesting feature of this old repair is that Cowan has identified the added piece as made from American walnut, with its diagnostic long fiber rays, while the original stock is the expected European walnut with its diagnostic short fiber flecks! It is possible that the final repair was made in the field by a skilled person. This would not rule out John Shields, or perhaps someone else, during the expedition, but more likely it was done after the expedition in a regular gunshop.

That the Lewis airgun was in the Lukens shop after the expedition may be the result of it having been returned to the only airgun maker in the Philadelphia area for repair. It may have been repaired there, probably by a local stock worker regularly used by Lukens, and remained as the property of the shop or it may have remained there because of the untimely death of Captain Lewis.

Obviously, an air pump accompanied the Lewis airgun on the expedition. However, if an air pump, and perhaps even an accessory pouch (see Austrian Airguns section of this website), had accompanied the Lewis airgun back to the Lukens gunshop after the expedition, it (they) almost certainly would have been separated there from the airgun, especially at the time of gathering goods for the Lukens's estate sale. These side items simply would have been among the many airgun accessories in the Lukens's shop and disposed of separately at the auction. Thus we would expect that the Lewis airgun would have been sold without a pump. The Beeman Girandoni was without a pump, pouch, or case.

Fig. 5. Right: Replaced middle thimble (right) from the Beeman Girandoni, compared with an unfinished middle thimble of correct original style (left) from an unfinished museum copy of the Girandoni air rifle made by Ernie Cowan. Note that the replaced thimble is simply rolled flat brass plate while the original style thimble, like the other thimbles on the Beeman Girandoni specimen, is a solid cast brass part. Beeman collection and photo. ©2005, Robert David Beeman

Fig. 6. Opened scarph joint in the forearm of the Beeman Girandoni. The wood at the left is original European walnut. The replacement wood at the right is American walnut. Beeman collection and photo. ©2005, Robert David Beeman

Fig. 7. Top view of female section of above scarph joint. Note the incredible thinness of the wood on the sides, actually tapering to less than paper thick.! Beeman collection and photo. ©2005, Robert David Beeman

It has been said that historical artifacts can sometimes speak to us through the ages. This gun tells us that not only does it have many special features and an old injury consistent with the recorded adventures of the Lewis and Clark expedition, but that, regardless of where it might have been in the meantime, it apparently was in America during the 19th century.

Figs. 8 and 9. Underside of the octagonal barrel showing the forward pin lug of the Beeman Girandoni air rifle. This lug had been torn open by great force. It is complete and evidently has been tapped back into a functioning position; too much tapping might have broken the lug off. ( Post-accident handling of the gun almost surely could not have been strong enough to cause such tear in the metal.) Note the consistent lengthwise marks of the original draw filing of the barrel on the bottom flats of the barrel (here shown on top). These flats evidently were not subject to the impact of the accident. The left barrel flat (shown in the bottom of the upper, magnified view and in the center of the lower view) reveals the overlaying marks of rough field filing as would have been made by a right handed person holding the gun, muzzle to the right, in a clamp or even on his knees. ©2005, Robert David Beeman

Fig. 10. Upper end of the barrel showing the irregular file marks made during field repairs of the impacted areas. Pits of the original impact injuries are still evident; running one’s fingertips along these apparently smooth flats reveals them to be bumpy and irregular. Only the upper and left areas were impacted. Original longitudinal draw marks, made during the manufacture of the gun, are still visible on the right hand barrel flat (and the flats on the bottom of the barrel). Note that the left hand end of the front sight was filed off flat during these improvised repairs. Beeman collection and photo. ©2005, Robert David Beeman

Turning to the barrel surface and sights, close examination reveals that the longitudinal draw file marks of the original barrel surface have been interrupted around the left side of the front sight and the left front flats of the octagonal barrel. This is dramatically evident when one runs their fingers across the metal of this area. The original draw file marks are crossed, or obliterated, by rough transverse file marks which indicate field trimming of impact gouges in the left forward area of the wrought iron barrel metal and replacement of the front sight. This is consistent with the note of Lewis that “her sights had been removed by some accedent. I put her in order and regulated her.” The rough nature and irregular angles of the forward filing marks strongly suggest that it was not a skilled metalworker such as the gunsmith/blacksmith Shields who did the work. He surely was too busy fixing other guns and important items that suffered more serious damage in the boat accidents. The file marks are exactly what would be expected from an unskilled worker seated and holding the gun across his knees. Perhaps it was Meriwether Lewis himself who wielded the file as part of his putting “her in order and regulated her.” The "regulation" would, of course, refer, at least in part, to adjusting the sights which he had returned to the gun. Most anyone familiar with open gun sights would have gently tapped down a side of the dovetail to secure the sight after adjustment and thus we would expect the sights to still be on the gun at the end of the trip - especially absent any note to the contrary. If he had made new sights, or had had Shields make them, surely there would have been some mention of that. Instead he just refers to putting things in order and simple regulating - as in securing broken parts of the stock, returning the sights, adjusting and securing the sights, and filing the gouged places in the metal.

The fact that the forward part of the barrel, barrel lug, cleaning rod, and thimble were injured would rule against the idea that the forearm simply was replaced due to age or drying cracks. Clearly this gun has been involved in a horrendous accident. The damages simply were not the kind of injuries that could be due to age, rough handling, or hunting or storage accidents. They are exactly consistent with the gun, covered and in company with several other items, being dashed into streambed rocks just the day before Lewis put the gun in order and adjusted a replaced sight. The temporary repairs speak of the kind that would be done in a wilderness setting.

Fig 11. Right hand view of the mid-area of the forearm of the Beeman Girandoni. The dark, damaged areas are suspected of being charring caused by excessive heat from a campfire. The bruises, gouges, and the wood missing along the upper edge of this section of the stock also attest to brutal field handling of this gun. Beeman collection and photo. ©2005, Robert David Beeman

I have noticed some interesting charring of the original parts of the walnut forearm of the Beeman Girandoni. This charring is exactly the type of damage that I have observed when I was attempting to dry wooden objects near a campfire during my own extended stays in the rugged Selway/Bitterroot wilderness of Idaho. Remember that such unmarked specimens of the Girandoni military repeating air rifles apparently were guns which had been diverted from the Girandoni shops to "gentlemen" civilians. Thus such guns would not have exposed to the rigors of military field life - including campfires. The "gentlemen shooters" of that period returned home each evening from hunting - they would not have been huddled around campfires trying to dry out equipment. However, this gun, which we think was on a wilderness expedition of several years, could indeed have been subject to such drying by a campfire, especially if that gun had been submerged - an example would be the time that a great deal of equipment was soaked or lost when three Corps of Discovery expedition canoes struck rocks and were swamped in the Jefferson River on August 6, 1805.

Although the Beeman Girandoni air rifle obviously has been cleaned and polished many times through the centuries, close examination of the entire specimen reveals, not only the rough field file marks, the major stock repair, and the replacement of the ramrod and its thimble, as described above, but a very large number of impact dents, bruises, gouges, and scratches. The air reservoir/buttstock is severely battered. These marks and injuries are what would be expected of a gun that spent a long time as a hard used tool in rugged field situations. It is a testament to the design and production of the gun by B. Girandoni that it still is in fine firing condition (except for possible, not easily detected, age weakening or corrosion of the inside of the air reservoir. This alone would preclude any present firing tests.).

Evidence Area 4: Accidental Discharges and Malfunctions

Brunot Island Accident:

Captain Lewis' first journal entry of the

expedition recorded his stop at Brunot Island as he began his descent of the the Ohio River in the expedition's

keelboat:

Recorded on August 31, 1803 (shown as August 30):

"Left Pittsburgh this day at 11 ock with a party of 11 hands 7 of which are

soldiers, a pilot and three young men on trial they having proposed to go with

me throughout the voyage. Arrived at Bruno's

Island 3 miles below halted a few minutes. went

on shore and being invited on by some of the gentlemen present to try my airgun

which I had purchased brought it on shore charged it and fired myself seven

times fifty five yards with pretty good success; after which a Mr. Blaze Cenas

being unacquainted with the management of the gun suffered her to discharge

herself accedentaly the ball passed through the hat of a woman about 40 yards

distanc cuting her temple about the fourth of the diameter of the ball; shee

feel instantly and the blood gusing from her temple we were all in the greatest

consternation supposed she was dead by [but] in a minute she revived to our

enespressable satisfaction, and by examination we found the wound by no means

mortal or even dangerous;….”

How could this have happened and what does this experience tell us about the Lewis airgun?

There are several possible explanations how the accident happened. First, it must be remembered that Lewis had to dig the airgun out of items stored in his boat, virtually at the beginning of the expedition. He surely was not much more familiar with the gun than those to whom he was displaying it. The men present at this demonstration would have been quite familiar with flintlock firearms. It would be natural for Lewis, or any of them, to put the gun on half cock in an attempt to make it “safe”. The notch on the tumbler of a typical flintlock firearm is notched so that the sear is securely held in the half cock notch even if the trigger is pulled. With such a firearm, one must pull the hammer back enough to release it before the hammer can be lowered to the resting position.

If the gun, which Lewis presented to them, had been a single-shot muzzle-loader, the men of the group could have seen if a ball had been loaded and not fired. Not being familiar with repeaters and not having any way to tell if a Girandoni system airgun had a ball in the firing position, such a shooter might not have appreciated that such a gun was indeed loaded. Also, with a Girandoni, getting a ball in the firing position only would have taken someone easily pushing the intriguing breech block across[22] while the gun was being passed about, but that would still require the very intentional cocking of the gun and being subject to the defective half-sear. Obviously the airgun did have a ball in the firing position. The simplest explanation for the accidental discharge would be that the airgun was put on half cock and that Mr. Cenas, thinking that it was in a safe mode, was horribly surprised when it fired at an unexpected moment due to a fault of that half cock.

Cowan also discovered that the Beeman Girandoni has a faulty half-cock! The large majority of the spur on the half cock notch which should hold the mechanism against release, even with a strong pull on the trigger, is simply broken off. While the gun indeed can be brought to half-cock, it rests there in a very precarious manner. The firing action can be released by a very light touch to the trigger or even a jolt. If the half cock position was faulty and thus can release the hammer, it can gain some momentum before the wedge hits the striker latch notch and the valve will open discharging the ball. The shot will not be as powerful as from full cock but could be strong enough to be dangerous. Again, at this time, Captain Lewis probably would have been unaware of any functional problems of the gun and probably did not even realize what had caused the accident. There is no indication that any Lukens air rifle has such a problem.

Fig. 12. Sear tip (yellow) locked into a properly shaped half-cock notch on the Girandoni tumbler (red). Note the full cock notch to the upper left. The sear tip locks into the full cock notch when the tumbler is rotated counter clockwise by cocking the hammer. Normal trigger pull then causes the sear to move down out of the open full-cock notch and release the tumbler to rotate rapidly clockwise and fire the gun. CAD diagram by Geoffrey Baker.

Fig. 13. Tumbler of the Beeman Girandoni. View from the gun’s right side. On the left are the full-cock notch (upper notch) and the half-cock notch (next lower notch). Note that the defective half-cock notch appears even more open than the full-cock notch. A very dangerous situation. Compare with the correct shaped half-cock notch in the colored figure above. (The working edge of the tumbler wedge just shows at the very bottom of the tumbler.) Beeman collection and photo. ©2005, Robert David Beeman

Fig. 14. Tumbler of the Beeman Girandoni flipped over to view it from the gun’s left side. At left is the tumbler wedge which, upon firing, transmits the energy of the mainspring which forces the tumbler to rotate counter-clockwise. The moving wedge pushes on the striker latch and causes the reservoir valve to release stored air. ©2005, Robert David Beeman

At right are the half-cock (left) and full-cock (right) notches. Clockwise rotation of the tumbler during cocking causes the sear tip to drop first into the half-cock notch and then into the full-cock notch. Note that about 1.5 mm of the half-cock notch lip is missing. Such an abnormally shallow notch, as found in this particular specimen, can only very precariously hold the tip of the sear. It cannot carry out this notch’s normal role of restraining the sear when the trigger is pulled. Thus this gun could fire most unexpectedly from the half-notch position. On the right is the full cock notch with its normal right-angle opening which allows a smooth, intentional trigger release and firing. Compare with the normal arrangement shown below. Beeman collection and photo.

Fig. 15. Left hand view of the sear and tumbler of a normal Girandoni firing lock mechanism in an European specimen of a Girandoni military repeating air rifle. The sear is engaged with the full cock notch. Compare this normal pair of cock notches with those of the Beeman Girandoni in the figure above. Note that the full cock notch is similar, but somewhat more open, on this normal gun but that the half-cock notch is much deeper and would serve to restrain the sear’s tip if the trigger were pulled. Photo by Geoffrey Baker of Girandoni SN 1493 (the "Nolan/Fisher" Girandoni).

There are other less likely scenarios which could have led to such a potentially deadly situation. The studies by Baker and Currie give us (personal communication, 25 October 2004 and Baker and Currie, 2006), for the first time, a full understanding of how the Girandoni firing mechanism works. If Blaze Cenas pulled back the hammer to a point where the wedge engaged the notch of the striker latch and then engaged the hammer with the half cock or full cock, the sound and feel would be similar to the sensations on a conventional flintlock firearm. If he pulled back the hammer to release it from half or full cock, while holding the trigger to release the sear, and lowered the hammer, as he would be familiar with doing with firearms, this would have allowed the tumbler wedge to put mainspring pressure, via the striker assembly, on the air valve. With the very strong mainspring of a Girandoni the valve can be opened even at fairly high pressure allowing some air to escape. This fills the space between the valve and ball and reduces the pressure difference between that space and the air reservoir.

The escaping air leads to less force holding the valve closed and the force of the mainspring, applied via the wedge pushing on the notch of the striker latch, can further force open the valve in an extremely rapidly building cycle. A slight hiss of escaping air suddenly increases to a point where the valve is fully opened and enough air blasts out to propel the ball from the barrel. The velocity would not be as great as when the gun is fired from full cock but it could be dangerous. With the large reservoir of a Girandoni all of the stored air would not be lost.

Thus we now see that just because of the special way the complex tumbler is built in the military versions of the Girandoni repeating air rifle, coupled now with a tank of pressurized air, an accidental discharge of air is to be expected when the hammer is lowered from the full cock or half cock positions.

Experience with firearms would have taught the holder of the gun to point the muzzle to the earth or at least not at anyone. However, when the airgun started to make a strange hissing sound, the startled shooter probably would lift the muzzle – just before the gun completes the very rapid cycling and the ball is propelled out! Even though they were familiar with the peculiarities of airguns, Geoffrey Baker, when testing[23] their replica Girandoni in early 2004, caused his fellow worker, Colin Currie, to jump with fear when they accidentally experienced the “startling noise and shocking report” of such a situation! (Fortunately without a lead ball.)

Another possible scenario, related to the broken half-cock notch, would involve Mr. Cenas cocking the gun to the position of the second click. With a typical flintlock firearm, this would be the full-cock, firing position. Cenas then pulled on the trigger, but as the gun actually was in the half-cock position, nothing happened. In frustration he may have pulled very hard on the trigger and turned around a bit to demonstrate his problem to Lewis. As he did this, his excessive pull broke off the thin ledge of the half-cock notch and allowed the gun to discharge in the direction of the distant ladies. Any experienced shooting rangemaster has seen exactly this kind of dangerous gun swing executed by frustrated shooters.

Whether the defective half cock notch was caused or discovered at Brunot Island, this defect could well have been a key reason why Lewis did not allow others (except for very rare use by Clark) to use the airgun from this point forward.

The nature of the Brunot Island injury really tells us nothing about the gun which caused it. As discussed at length earlier (Beeman, 2004), even the perception of being injured can cause the kind of human reactions recorded. Note that Lewis states that he pumped up the airgun just before the firing demonstration. It is probable that he did not apply the thousands of pump strokes needed for a full charge at that time. Thus considering what effect a Girandoni system airgun could have had at highest power is irrelevant. If the discharge occurred due to improper lowering of the hammer on a Girandoni, such a discharge also would have been at reduced power.

Evidence Area 5: Firing and Function Problems.

The Airgun Demonstration to Judge Rodney. Wheeling, September 8, 1803.: Rodney recorded that Lewis lost all the air at the “first fire”. We know now that this could simply have been the result of very low air pressure in the air reservoir. When the air pressure gets so low that the air valve has very little pressure against it the valve stays open longer on each shot until finally the last air is released all at once, resulting in a very weak discharge. The air dumped on this first fire may have been residual air from the Brunot demonstration only a week earlier.

Having low pressure in the air bottle could have several effects. As noted, one is the accidental dumping of air which occurs when there is not enough pressure to resist the mainspring when the cocking lever is forward. Low pressure also could result in greater condensation and less wiping force on the striker pin. It was discovered in our specimen that the brass guide for the steel striker pin has an iron liner sleeve. Such condensation and lack of enough pressure to very forcefully push the striker pin could mean corrosion would develop on this steel pin and/or on the iron of the striker pin sleeve and cause the pin to stick in the open position[24]. Some condensation corrosion here would have been expected as a result of the shooting demonstration at Brunot Island the week before. Thus the enigmatic failures are now perfectly explained.

Lewis probably learned at Brunot Island and later that by just working the cocking lever several times, while the trigger is held down on an empty tank, that he could restore operation of the gun. While he may not have realized, at least at first, that this could result from freeing a stuck striker pin; he may have discovered this detail later. It also is easy to remove the lock plate, loosen the striker latch guide screw behind the trigger, and thus slip out the striker assembly for easy and rapid cleaning. Either of these simple acts of freeing a corroded striker assembly could be the simple, quick adjustment that Rodney referred to at Wheeling. Also, although the striker latch guide screw has no adjustment role, it sometimes becomes loose. When Lewis had the problem, he may have noticed that this screw was loose, tightened it and then when the airgun was pumped again, the new pressure in the reservoir would assist the closing of the valve and allow shooting to continue in a normal manner. This would also have been true if he had done the meaningful cleaning or working of the striker pin.

Ironically, Lewis may have inadvertently often kept his airgun in an undependable condition, due to condensation corrosion. Soldiers, who had to depend on the air rifles for their lives, might have had this problem much less often because they used their guns more often and they were trained to keep these pins polished and lubricated.

Fig. 18. Rear surface of the receiver of the Beeman Girandoni. The little steel striker pin tube in the dead center of the receiver may have been the cause of sticking valves, esp. at low air pressure. The striker pin must be fitted very closely into the striker pin tube as this is one of only four points where air could leak. Air pressure is present here only during the milliseconds of discharge and leakage is prevented only by friction and lubricant. The slightest bit of rust or stickiness between the closely fitted iron striker pin and this steel striker pin guide could prevent, or retard, movement of the striker pin and thus prevent firing or it could cause air dumping. The bean-shaped black area above the striker pin tube is the entrance to the air passage which was drilled and filed into the solid metal casting when the gun was made. The valve body of the air reservoir screws onto the threaded shaft presented here, separated by the cow horn gasket mentioned in an earlier caption. Beeman collection and photo. ©2005, Robert David Beeman

The important point here is that it has now been shown that it is easily possible for a Girandoni system airgun to have had exactly the kinds of air release problems and field adjustments described for the Wheeling airgun demonstration. This removes another very important question about the credibility of the Rodney account. And it is significant that these actions occurred, and were recorded, eight months before the beginning of the wilderness section of the trip. By the time the expedition began in earnest Lewis and several expedition members could have become quite familiar with the airgun and would have begun to take its operations, actions and features for granted – matters not in themselves appropriate for comment in the journals.

Bud Clark, the great-great-great grandson of Captain William Clark, inadvertently provided (personal communication, 15 August 2004) a very realistic insight into the possibility that Lewis sometimes used the airgun at improperly low pressure. While Bud was acting the role of Captain Clark, in the 2003-2005 real life re-enactment of the original expedition, he was anxious to know (via email and satellite phone from the trail!) if I could provide him with a replica of the Lewis and Clark airgun so that he could demonstrate it, very much as Lewis actually did, at various public displays. He pointed out that he didn’t need a gun which would pass a full high pressure test as he would just be “charging it only enough to demonstrate its function”.

Evidence Area 6: Markings on the Beeman Girandoni

Fig. 19. Underside of the forearm of the Beeman Girandoni, showing the carved "lightning bolt" lines which may have been added during the Lewis & Clark expedition. Cowan reports that Indian experts indicate that such marks very likely were made to increase the “powerful magic” effect of the airgun to the Indians. ©2005, Robert David Beeman

Fig. 20. Middle underside of forearm of Beeman Girandoni, showing "string of beads" carving of unknown significance. The "lightning bolt" and "string of bead" lines shown in the above two figures are not found on other known specimens of the Girandoni military repeating air rifles. Note, especially in places like the bottom of the carved loop and the defect in the "string of beads" shown in Fig. 19 above, and the tiny gouge marks around the lower left lightning bolt in Fig. 19, that these extra decoration marks clearly were not made by a master gunstock worker with fine stock carving tools, but rather they are the nature of carving that one would expect from someone very good with a very sharp, ordinary field knife - as on a wilderness expedition.

Even these special carvings have been very carefully copied by Ernie Cowan onto the four museum copies of the Beeman Girandoni. Beeman photos and collection. ©2005, Robert David Beeman

As shown above, the Beeman Girandoni has some unusual carved lines on the underside of the stock’s forearm, between the trigger guard and the first thimble. Nothing like them appears on any other known Girandoni system air rifle. Ernie Cowan and Rick Keller, in consultation with museum experts on Indian marks, indicate that these probably represent lightning bolts and may have been carved there, during idle expedition time, to increase the perception of “powerful magic” for the airgun.

I consider these "lightning bolt" markings as even stronger support for ownership of this gun by Captain Lewis than if we had found a gun with his name carved on it. A gentleman might have his name carefully inscribed on the side of a gun's lockplate by a skilled engraver, but gentlemen did not carve their names into gun stock wood! However, given the periods of boredom inherent in the stalled periods of such an expedition, adding some discreet symbols of such significance would seem very understandable. Close examination of these marks reveals that they were made by a very sharp knife and that they are very old, surely made in the same period as the gun itself. They certainly are not the kind of decoration, and do not represent the kind of skill, that would have been contributed by a professional stockmaker. With his attention to detail and concern for combat readiness, Lewis probably kept his knife very sharp. These marks very likely reflect some camp bound attention to the airgun by Lewis himself.

(I can well relate to such unnecessary detail work during periods when one is bound to a location in the wilderness. As a coincidence, I was snowbound for considerable periods, while researching elk migration during the 1950s, on trails very close to those of the Corps of Discovery in Idaho's Lochsa/Selway Bitterroot Wilderness Area. I spent many hours with my own sharp knife, making such superfluous things as a tiny, intricate, buckskin pouch for my Hastings triplet hand lens.)

In the area of markings, we also should consider what is NOT marked on the airgun. Although the airgun was mentioned in the journals more than any other arm on the expedition, obviously the center of a lot of attention, no mention was ever made of the mark of that famous maker. The journals reveal that Clark had a personal flintlock rifle, of much lower interest, referred to as the Small rifle (made by John Small), but there was no mention of the airgun's maker. Throughout the history of guns, their users commonly have referred to their weapons by the name of the maker: "my Colt, Winchester, Purdey, Garand, Springfield, Mauser, Luger, Sharps, Thompson, Gatling gun", etc. etc..

This is strong evidence that Lewis' airgun was one of the small number of military rifles (reportedly up to 200 guns, but probably a far lower actual number) known to have been slipped to private buyers by Girandoni before his death in 1799. These guns certainly would have been without any maker's mark or serial number and almost surely would have been plain and unornamented. That would eliminate all "surplus" or "lost", Girandoni-marked military air rifles and would narrow the field of candidates to only a few unmarked military specimens, made in the proper time window, most of which would fail or be lost, and virtually all of which would never reach America. I certainly concur with the strong opinion of Dean Fletcher, a student of American 20th century airguns, (personal communication, Lewis Reinhold, 23 Dec, 2005) that Lewis' airgun probably was an unmarked specimen of the Girandoni repeating airgun system. Our specimen is most unusual in being a true military model, plain and unadorned, of the appropriate sub-style/timing, without that famous maker's "G" and four digit serial number - just as we would expect of Lewis' airgun. It apparently is one of only two known unmarked Girandoni military model repeating air rifles.

Reference to the Airgun in the Expedition Journals

A firearm-based bias has produced a huge barrier to understanding the matter of the Lewis airgun. Firearms generally operate at full power but a pneumatic airgun can operate within a great range of power. Our understandings of what was recorded, and our expectations of what should have been recorded, in the expedition journals may have been deeply colored by the concept of an airgun operating only at high power. This bias especially is true of much of the modern consideration of the Girandoni airgun which has centered on, and assumed, operation at its potentially high power. The lack of experience by Captain Lewis with any airgun, coupled with a probable lack of information, would have been a tremendous factor in not using his airgun to its potential. Larry Hannusch, while now supporting the idea of a Girandoni for Lewis (personal communication, 17 November 2004), has reflected that our new considerations that Lewis probably was unfamiliar with airguns, and that the airgun sometimes may have been operated at less than potential power, got him to thinking in new directions, including appreciating that there is a HUGE difference between an airgun’s potential firepower and its practical firepower.

We know that Captain Lewis had real problems with the operation of his airgun; probably even more problems than were recorded in the journals or by visitor Rodney. Just the problems of operation and hazardous use at Brunot Island and Wheeling, before the wilderness phase of the expedition even began, may have been the keys to why we don’t read about the features, great firepower and wonderful action of the Girandoni airgun. With just those bad experiences in mind, would you bet your life, or even the critical success of hunting, on a gun that had so performed? One would expect that Lewis would have made the decision, after the problems of those first two shooting shows, even before leaving St. Louis, that the main value of the airgun would be for demonstrations to impress the natives. Let those potentially dangerous viewers admire this strange gun and “dread the magic of the owners” while he, and the other members of the expedition, may have been quietly unimpressed with it. They may have considered it only as a rather undependable “new fangled gadget”, rather than as a wonderful tool over which to wax eloquent! So, it proceeded on, perhaps only working after Lewis would clean and loosen up the striker rod and valve spindle and pump it, out of view, only as needed to produce a good show

Along the same line, there is a possibility that Captain Lewis, and the expedition party, may not have taken the airgun seriously. Therefore they would not have been motivated to regularly contribute the large amount of hand pumping necessary to bring it to its full potential. (Even modern users of old air canes find it exhausting to apply even the roughly 300 strokes necessary to charge their small reservoirs). This would explain many things, from continued poor performance, to lack of comment, and to a lack of serious consideration of the airgun for hunting or defense[25]. This gun, which had the potential to be such a deadly, high-firepower “assault rifle” (Gaylord, 1997) may not have been given a fair chance and/or it may not have been suited to solitary use on a wilderness expedition without proper training, the presence of experienced airgun personnel, and a wheeled air pump and/or a running supply of pre-charged bottles. (We should note here that while a Girandoni could be compared to an "assault rifle" in comparison to the muzzle-loading black powder firearms around the beginning of the nineteenth century, it truly would be absurd to so consider such a gun two centuries later in our present period of rapid fire and full automatic firearms!)

I think that it is very probable that the early problems with the airgun served to teach Lewis how to use and maintain it. Ernie Cowan and Richard Keller (personal communication, 3 November 2004) feel that the airgun was fully appreciated and that pumping it up to high power, to maximize the impression of the demonstrations, would not have been that unlikely, especially if one considers the spare time that may have been available at times and that one could use the services of a slave and line soldiers. The expedition crew would just have taken it for granted after first learning of its features, operation, potentials, and shortcomings. The leaders and scribes of this journey commented very little on the details of other expedition items. Their charge was to record the findings of the trip, so it would be understandable if they did not do more than note some of the events involving the airgun. And, there are major time gaps in the journals.

As for hunting, it is possible that the airgun was not always up to top power, and even if it was, it would still have been less powerful than trusted and familiar firearms. Hunting was not a matter of sport for these men. While a serious wound , even a wound resulting from a shot from a partially empty air reservoir, would take an enemy soldier out of battle, only quickly lethal wounds were appropriate to hunting. Lewis apparently did not do much hunting and, wisely fearing it misfiring due to its hazardous condition, plus wear and breakage, it is probable that he would not have allowed the airgun to leave his side. It was just too hazardous for regular handling by others and it had just too much possible vital strategic importance to be subject to breakage during frequent use or to be exposed to too much familiarity by the natives. Only his trusted and bright partner, “Captain” Clark, was ever also allowed to fire it.

"The Key to the

American West" or

"The Most Important Individual Gun in American History"

The title above is meant only to parallel the title "The Gun That Won the West" - The Lewis airgun certainly didn’t “win” the West – that was done over many years with strategy and by great intimidation and violence from Colt and Winchester firearms. It is interesting to note that the significance of those firearms also came from being repeaters - but more than a half century after the Girandoni repeating air rifles! And it didn’t ”open” the West – much of the West had already been opened for trade with the natives by British traders. However, that truly was minor compared to what was accomplished by this expedition. This airgun is all the more remarkable in that it apparently developed its "firepower diplomacy" without having killed a single person.

It certainly can

be said that the airgun shooting demonstrations on the expedition were an enormous success. The

airgun created great respect for these travelers. For one example:

Private Whitehouse noted in his

expedition journal entry of August 30, 1804, when Captain Lewis demonstrated his

airgun to the Yankton Sioux in the Calumet Bluff area along the Missouri River,

apparently on the Nebraska side:

"Captain Lewis took his Air Gun and shot her off, and by the Interpreter told

them there was medicine in her, and that she could do very great execution. They

all stood amazed at the curiosity; Captain Lewis discharged the Air Gun several

times, and the Indians ran hastily to see the holes that the Balls had made

which was discharged from it. at finding the balls had entered the Tree, they

shouted a loud at the sight and the Execution that was done suprized them

exceedingly." The Indians would not have been able to comprehend the

gun shooting again and again and again without reloading - and without flash or

smoke.. This would have been terrifying considering the "execution" that

such a flashless, quiet gun had demonstrated as its potential!.

©2005, Robert David Beeman. Painting by

Warren Lee.

Air Power Diplomacy -Captain Lewis' "Assault Rifle"- The Key to the American West. Evidently Captains Lewis and Clark realized rather early in the expedition what a great impression could be made by dramatic demonstrations of the amazing properties and astonishing firepower of their "magic" airgun . Appearing in formal formation, flags and banners flying, dressed in their colorful full dress military uniforms with towering tasseled chapeaus, fancy coat tails, brilliant sashes, bright braid, and shining medals, the Corps built a tone of high theatre around the previously loaded and charged repeating air rifle. This painting illustrates one of these shows, as described by Private Whitehouse in his expedition journal entry of August 30, 1804, in which Captain Lewis demonstrated his airgun to a large group of high ranking Yankton Sioux in the Calumet Bluff area along the Missouri River. Some of the honor guard braves have run to the distant target tree and are incredulously reporting that numerous lead balls are buried in the wood even though the gun had not presented any smoke or fire and relatively little sound. Captain Clark, in later journal entries, made it clear that they implied that the Corps had a large number of these guns. (See notes about this painting and how to obtain copies at the end of this paper.)

It is apparent that many

Indians, if they had seen such an “assault rifle” in action, would have been

anxious to get aboard the expedition boats to see if the group had a supply of

these amazing guns. Captain Lewis always was careful to keep them from fully looking

around on the boats. If the trip leaders were flaunting a rapid fire Girandoni,

especially if they were careful never to let the natives see the gun run out of

balls, then “dread of the owners” of guns which apparently could fire an

infinite number of times with incredible speed, probably was a major

strategic factor in this little group of explorers never being attacked during

the long duration of the trip.[26]

If any Indian tribe had taken the expedition's weapons they

would have become the most powerful tribe in the regions. That the mere presence

of the airgun could restrain hostile action was demonstrated by Captain Clark's

note of September 25,

1804 concerning the Teton Sioux after he had noted that they feared that these

Indians were detaining them in order to rob them or worse: "Capt. Lewis

shewed them the air gun. Then we told them that we had a great

ways to goe &that we did not want to be detained any longer".

Surely

this meant that the airgun should be considered as a strong reason why they

should not be further detained. Clark's thinking was again revealed by his writing on April 3, 1806,

on their return journey when they were dealing with troublesome tribes on

the Columbia: "Lewis

fired the Air gun which astonished them in Such a manner that they were orderly

and kept a proper distance during the time they Continued with him...".

Clark clearly is saying that the airgun was the only thing that kept the Indians

at a safe distance. The Indian method of attack was to rush their enemy after

the defenders fired their single-shot guns.

These records

are some of the strongest evidences that the airgun was a Girandoni system

repeater; it seems almost impossible that a single-shot air rifle of relatively

small caliber would have had such

intimidation value.

The above passages may be some of the most least appreciated, but most important, notes in all of the expedition journals. Captain Clark, and undoubtedly Captain Lewis as well, clearly realized the potential of the airgun, backed up by an assumed further inventory of them, as a tool of "firepower diplomacy". The presentation of the airgun by Captains Lewis and Clark certainly was not a casual matter, but rather a calculated, considered strategy that apparently paid enormous dividends.

This is the first presentation of the idea that the expedition's airgun, as an "assault weapon", backed up by an inferred stock of more of them (or even perhaps the implication that all of their long arms could fire indefinitely without reloading), may well have been basic to the success of this important expedition. Lest we think that this idea might not have been inherent in the thinking of the expedition's leaders, we need only consider Captain Clark's remarks above and the previously unappreciated insight to Clark's thinking revealed during a frightening and complex confrontation with Chief Black Buffalo, commanding hundreds of aggressive Teton Sioux, on Sept.25, 1804, near the very start of the trip. Angered by threats, Clark recalled that "I felt My Self warm& Spoke in verry positive terms". Sergeant Gass recorded that Clark's "verry positive terms" included that "he had more medicine on board his boat than would kill twenty such nations in one day". For the very first time, we finally have an understanding as to what "secret weapon(s)" Clark was alluding. The implication apparently was that they had a large supply of these wonder guns right there on his boat. And, as noted, Captain Lewis, only three weeks earlier, had warned other Sioux viewing an airgun demonstration that "there was medicine in her, and that she could do very great execution". "Medicine", of course, was an Indian term referring to great, generally inexplicable, force - the kind of force which could be presented by many smokeless, fireless guns which could fire lethal, highly accurate balls with incredible rapidity, apparently an infinite number of times, without loading - yes, with enough "medicine" to kill, execute, twenty nations of Indians in one day!