“Proceeding On” To The Lewis and Clark Airgun - III

By Robert D. Beeman Ph.D.

NOTE: This is NOT

the latest info on the Lewis and Clark airgun. For that please click on

the Lewis Assault Rifle

section and follow that up with the section on Austrian Airguns!

Partially updated, revised,

enlarged, and

corrected from the article of the same title in The

Second Edition of the Blue Book of Airguns, 2002.

This chapter established 23 March 1999. Latest update 6 May

2008.

UNDER CONSTRUCTION - NOT YET FINISHED!

(Note especially that figures are being added and rearranged; figure

numbers are not yet completed.)

This

material supersedes my previously published material!

Please DO NOT use or quote earlier, outdated material!

Exciting new evidence recently has led to another airgun as the actual airgun carried by Lewis and Clark. Click on this blue title to view the Lewis Assault Rifle section of this website. Despite the fact that new information and additional research has superseded the preliminary indication that Lewis carried a single shot air rifle made by Lukens, the following paper gives some very important basic information about the search for the Lewis airgun, Lewis' equipment gathering period in Philadelphia, the Lukens/Lewis connection, and much new information on the Lukens and Kunz airguns of Philadelphia. It is basic to understanding the matter of the Lewis air rifle.

Material on Girandoni Austrian Repeating Military Air Rifle and other large bore antique airguns is also presented in another section of this website. Click on the title "Austrian Big Bore Airguns" to view this big NEW section.

Fig.

1.Captain Meriwether Lewis

Oil painting by Charles Willson Peale. Courtesy of

Library of Congress

NOTE: A preliminary full set of illustrations may be viewed in the Second Edition of the Blue Book of Airguns (cited in the Literature Review section of this website). Some are in progress of being posted here. The remaining illustrations, plus some that have never before been published, and captions are in progress. (However, no figures are missing - if you cannot see some of the images, this probably is due to a conflict between the Microsoft Front Page program, used to create this website, and reading programs on your computer. Firefox and Safari servers seem to have a special problem with this material. If you cannot see some of the images, please send details as to what figures and as what server you are using to: Website@Beemans.net )

Most Americans are not aware that Captains Meriwether Lewis and William Clark carried an airgun during their famous expedition of 1803-06 into the Pacific Northwest. Actually, there was no widespread public announcement of this gun until Twaites' 1904 rendition of the original journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition and the more widespread and definite rendering of those journal by Moulton in 1983-2001. Moulton's edition of the Lewis and Clark journals has 39 references to this airgun. Certainly this gun is the most important individual airgun in American history and perhaps the world. It joins the Deringer pistol which killed President Lincoln, and the Italian Carcano rifle which killed President Kennedy, as one of the most important individual guns of any kind in American history. And we can be a good deal prouder and happier about this gun. This national treasure seemed to have disappeared in the last weeks of 1806 when Captain Lewis sent it in Box No. 2 of two boxes to be taken from St. Louis to Washington by a Lt. Peters[1] (Thwaites, 1904). It has taken almost two centuries to apparently crack the mystery of its identity.

Until recently, I felt, and stated (Beeman, 1977), that the identification of this airgun had pretty well settled on a .32” caliber air rifle (fig. 2) made by Isaiah Lukens, horologist and gunsmith in Philadelphia. Then, Doug Wicklund, firearms curator at the wonderful new National Firearms Museum at the National Rifle Association headquarters in Fairfax, Virginia, told me that he had heard of new journal information from that expedition, in which it was stated that the airgun was the same caliber as the soldiers’ rifles. No reference to the airgun’s caliber had previously been reported. It had become a matter of historical faith that the soldiers in the Corps of Discovery, as Lewis and Clark’s soldiers were known, were carrying U.S. Model 1803 rifles, which were .54” caliber. A .54” caliber airgun (fig. ), which could date back to 1803, had been found among undocumented specimens in the National Firearms Museum and it was suspected that this could be the Lewis and Clark airgun (Beeman, 1999).

Doug’s comments stimulated me to review my files on the Lewis and Clark airgun. It soon became clear that there are a number of contradictions and that some published notes must be in error. Interest in the Lewis & Clark expedition recently has much increased, certainly due, at least in part, to Steven Ambrose’s bestseller book, Undaunted Courage (Ambrose, 1995) which provides a wonderful, popular account of the expedition. And the bicentennial of the expedition created special interest. It seemed time to try to improve the record, so I resumed my research, begun, as note below, in 1976, about this gun.

Mrs. Beeman and I “proceeded on” (a now peculiar term which appears many times in the original journals of the Lewis and Clark expedition) to the Eastern United States to more closely examine some of the actual guns suspected of being the Lewis and Clark airgun and to research the involved literature and records at the Library of Congress and various museums. We were determined to at least shed more light on the interesting airguns that have been suspected of being this famous airgun.

A bit of personal perspective is in order. My interest in the Lewis and Clark airgun had its most serious beginning in January 1976 when I was visiting a fellow collector in Philadelphia, the late Henry Stewart Jr., who is best known for his collection and incisive studies of revolving firearms and blunderbusses. While we were working together in his gunroom, Henry excitedly bare handed me the Lukens air rifle that Wolff (1958) illustrated as item 4 in his figure 63. Henry indicated that he was about to publicly identify it as possibly being Captain Lewis’ airgun.

A). Right hand side, lock area of Lukens DNH. Lock at

rest.

B). Full length, right hand view.

C). Left hand side, lock area.

![]()

D). Left hand side of buttstock air reservoir.

Click on thumbnail image for larger view. Use landscape

format for printing.

Fig. 2 A-D. Views of the Lukens DNH air rifle. Bottom two photos by R. Beeman ©2001 Robert David Beeman., top two photos by Virginia Military Institute.

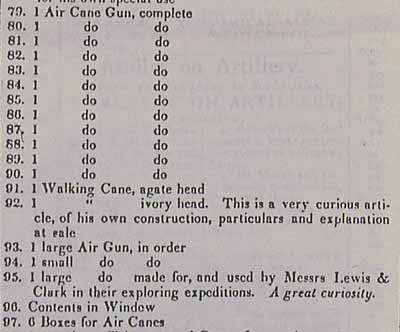

Henry Stewart at first felt that Isaiah Lukens had made this gun and that it may have been loaned to Meriwether Lewis for the expedition. Henry based his conclusion about Lukens on an incredible piece of luck that resulted from his intensive search for information on the Lewis and Clark airgun. It had been suggested that he check the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia. Upon inquiring there about Isaiah Lukens, a Mrs. Wumwreth said, “oh, yes, we have a pamphlet here on the sale of his effects”! That booklet announced the sale of the effects of Isaiah Lukens’ estate on 4 January 1847 (Fig. 3). Item #95 was “1 large air gun made for and used by Messrs. Lewis and Clark in their exploring expeditions”. The Lukens’ “Kentucky Style” air rifles, discussed in the present article, are indeed fairly large airguns, but they are only marginally large bore. Stewart (1982) later reported that his friend, Bruce Madson, found an ad for that estate sale in the Pennsylvania Inquirer and Gazette of January 4, 1847 which led him to a report of the money paid for the various items. Unfortunately, item #95, the Lewis and Clark airgun, apparently was withdrawn from the sale. Stewart could not trace that gun further.

Fig. 3. Section of the Lukens estate sale notice. Note reference to the Lewis and Clark airgun as item # 95..

In the February 1977 Monthly Bugle of the Pennsylvania Antique Gun Collectors Association, Stewart published a copy of that announcement, concluding that the Lukens shop probably was the source of the Lewis and Clark air rifle, but he did not say that this gun was the one.

Stewart gave an unpublished talk on airguns to the annual meeting of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation when they held their annual meeting in Henry’s home town of Philadelphia in August 1982. By then, Stewart had developed serious doubts that the Lukens DNH airgun actually was Captain Lewis’ airgun. Like Charter Harrison, the previous owner, he felt that the double neck hammer must have come from a U.S. Pistol of 1836 and thus must have been added after 1836, and he could not find any features which clearly pointed to this particular Lukens airgun as the very one carried by Captain Lewis. In this talk, Henry twice stated “I do not claim it as the Lewis and Clark gun ….. but we now know who made it, whether it is Lukens or his man Kunz….”

Halsey (1984) reported that Joseph Saxton, a prominent Philadelphia friend of Lukens, obtained many of the items of the Lukens estate, including some of the air canes. As a close friend, he may have been able to have certain items withdrawn from the estate sale, such as the Lewis and Clark airgun. Craddock Goins, a former curator of military history at the Smithsonian Institute, found old records that revealed that one of Joseph Saxton descendants, Joseph Saxton Pendleton, loaned some of the memorable items to the Smithsonian in the early 1900’s. These items were returned to the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia sometime later. Some of the estate items, including an air rifle, made their way into the airgun collection of Charter Harrison in Milwaukee. He may have acquired these from Saxton’s descendants, or the Franklin Institute, by trade or purchase.

How had the Lewis and Clark airgun gotten back to Philadelphia? A number of the expedition’s specimens, such as Indian artifacts and skeletons of mountain sheep, ended up in Charles Willson Peale’s Natural History Museum in Philadelphia. Stewart suggests that apparently what happened is that Lt. Peters, carrying these natural history specimens, as well as the airgun, was told by President Jefferson to stop in Philadelphia and give the natural history items to Peale instead of bringing them to Washington or Monticello. Lt. Peters, or perhaps Peale, apparently returned the airgun to its source, Seneca and/or Isaiah Lukens. Peale kept these artifacts and natural history items in his Natural History Museum in the upper floor of Independence Hall for many years, along with his famous portrait paintings. When he finally couldn’t afford maintaining the museum anymore, he sold the natural history collection to the famous showman P.T. Barnum.

The above airgun may be the DNH Lukens air rifle which G. Charter Harrison, who evidently was America’s first really serious airgun collector, had identified in the May and June 1956 issues of Gun Report as the Lewis and Clark airgun. Not having had the advantage of seeing other Lukens or Kunz airguns, Harrison thought that the most unusual hammer lug of the Lukens DNH airgun may been made by John Shields, the expedition’s blacksmith/gunsmith, and suggested the idea that this was part of Shield’s ingenious repair of the “main spring” of Lewis’ air rifle. Then, in the November 1957 Gun Report, he reversed himself and designated the Kentucky style ball reservoir air rifle (figs. 22-24), illustrated as item 1 in the same Figure 63 of Wolff (1958), as the Lewis and Clark airgun. As a result of that conclusion, Harrison presented the Kentucky style ball reservoir gun to the Smithsonian Institute as “The Lewis and Clark Air Rifle” and apparently sold the Lukens DNH gun to Henry Stewart, probably via my long lost airgun collecting friend, Warren Moore (author of Guns by Warren Moore, 1963). After Harrison’s mental health collapsed, his collection, as illustrated in Wolff (1958), became scattered as his wife sold off pieces to pay his medical bills. However, in the 1970s when I painstakingly traced and purchased most of Charter (Nick) Harrison's scattered collection, two of the key candidates for the honor of being the Lewis and Clark airgun already had eluded me! When Henry Stewart passed away on October 12, 1988, his fabulous gun collection, about 800 pieces, the backbone of which is a truly wonderful collection of revolving firearms, plus several important airguns, went to his alma mater of 1935, Virginia Military Institute in Lexington, Virginia. (The VMI website concerning this collection is at http://www.vmi.edu/museum/HMS.html.)

The late Henry Stewart, and those who since have considered the above Lukens air rifle, have had an enormous advantage, not shared by Harrison and other students of this matter. That is, by the time that Stewart had published his paper (Stewart, 1977) claiming Lukens as the maker of Captain Lewis’ air rifle, he had managed to collect not only the “original” Lukens DNH rifle, discussed above, but also another air rifle bearing the Lukens name, plus two other Kentucky style air rifles marked Kunz. These rifles are almost identical. Three of them are shown in figure 4. They clearly seem to show an evolutionary series from the same school of airgun design. By the time that Henry Stewart left us, he had collected a total of two Lukens air rifles and six Kunz air rifles, as well as several Lukens and Kunz air canes. At this time, I know of only three air rifles marked Lukens, and only three Kunz air rifles, outside those in the Stewart/VMI collection. I suppose that it is not too surprising that Stewart may have gathered almost all the surviving specimens from the Lukens/Kunz shop(s). Stewart lived right there in Philadelphia where the guns were made for, or at least sold to, local customers. And, once Henry Stewart became intrigued with the possible Captain Lewis/Isaiah Lukens connection, his very determined nature would have driven him to quietly locate, and obtain, every possible specimen - and price was no object to Henry Stewart. Now, we have the advantage of seeing what features were characteristic of airguns from these makers.

Another candidate for the Lewis and Clark airgun has been displayed at the Fort Clatsop Lewis and Clark museum in Oregon. In Stewart’s 1982 talk, he indicated that the “Clatsop” airgun is an outside sphere air rifle and that it had been purchased from Charles Stone of Virginia City, Nevada for $225 on June 26, 1962. The Clatsop museum then purchased an airgun pump from Leonard Clayton of Napa, California on August 12, 1965 and displayed the pump and this ball reservoir airgun as the type of airgun equipment carried by Lewis and Clark. Roy Chatters, of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation, studied the question of the Lewis and Clark airgun at length. He first discussed his findings in an article entitled The Enigmatic Lewis and Clark Airgun (Chatters, 1973). This was followed by The Not So Enigmatic Lewis and Clark Air Gun, in the May 1977 issue of We Proceeded On, the journal of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation. In the latter article, he reported that he had discovered that Henry Stewart was working on the same question and that he had come very close to some of the same assumptions. Since 1982, Robert and Toshiko Beeman carried on the search and research for the Lewis airgun. We were alone in this endeavor until about 2002.

Let’s review the clues that we have concerning the nature of the Lewis and Clark airgun. First is the matter of power. I could not find any journal references to the airgun actually being used to hunt deer or even small game. Stewart (1982) reported that Volume One of the Twaites edition of the journals has notes on pages 240 and 241 that a deer was killed with the airgun. My examination of those pages revealed no mention of the shooting of a deer with the airgun. There was mention of a deer being shot on page 240, but not with the airgun. However, the journal reports do indicate that Lewis’ airgun had significant power. First, there is the famous incident at the beginning of their trip where an outside visitor accidentally discharged the airgun. The fired ball produced a gushing flow of blood from a furrow, of a depth of about a “quarter of the diameter of the ball“, along the head of a woman some forty yards away. Second, when Lewis accidentally was shot through the buttock by one of his own men while hunting, he thought that Indians had attacked him. He reported: [I] “prepared myself with a pistol, my rifle, and my airgun, being determined as a retreat was impractical to sell my life as deerly as possible”. Third, Whitehouse’s journal for August 30, 1804 mentioned that the Indians were amazed, after one of Captain Lewis’ demonstrations of the airgun, that “the Balls had entered the Tree[2], they shouted a loud at the sight…”. Fourth, the rifle must have been suitable for signaling. Whitehouse’s journal for August 7, 1805 reported that Captain Lewis “fired off his air rifle several times” so that a lost man “might hear the report”. Perhaps the gun made more sound than would be expected when it was fired without a projectile. This journal report indicates that the airgun's report would have attracted the attention of a lost man in the quiet of the wilderness. However, I suspect that the airgun was chosen as a signal gun in this incident, not because it was louder than the available firearms, surely it was not, but rather because it did not use up any precious gunpowder. Martin Orro (personal communication, 30 September 2004) noted that his replica Lukens DNH air rifle makes a much louder and unusually distinctive report when fired without a ball and that this model can be "dry-fired" repeatedly, more than once a second! Such a staccato of special sounds when Lewis "fired off his air rifle several times" would be a very attention getting signal indeed.

It repeatedly has been suggested that this airgun could have been a bellows gun because of Capt. Clark’s journal entry for June 9, 1805 that stated: “The black Smiths fixed up the bellowses & made a main Spring to Capt. [Lewis’] air Gun, as the one belonging to it got broke”. However, using this entry to conclude that the bellows being discussed was the power mechanism of the airgun belies what it says and overlooks other entries, including Lewis’ own entry for the same day which said “as we had determined to leave our blacksmith’s bellows and tools here it was necessary to repare some of our arms, and particularly my Airgun the main spring of which was broken…. “. Having himself clearly distinguished between the blacksmith bellows and the main spring of the airgun, there should be no doubt that what was meant was that the blacksmith set up a blacksmith’s bellows for his mainspring repair. Also, the reference to leaving the bellows behind would be inappropriate if the bellows was part of the airgun - or, as been suggested by others, that the term “bellows” meant the separate air pump that is needed to charge most pneumatic guns. Both Captains Lewis and Clark referred to bellows and, as just noted; Lewis even specified “blacksmith’s bellows”. The two "gunsmiths" on the expedition actually were blacksmith/gunsmiths - a very common combination in those days.

Wood and Thiessen (1985) report the narratives of Charles McKenzie whose visit to the Hidatsa and Mandan Indians in 1804 overlapped that of Lewis and Clark. McKenzie reported that “The Indians admired the air gun as it could discharge forty shots out of one load-”. Given only the clue of forty shots on a single charging, it is clear that this airgun only could have been a pneumatic with a large air storage reservoir. This entry emphatically rules out the possibility that it was a spring piston airgun or a bellows airgun.

The air rifle apparently was accurate, thus it probably was rifled. If this gun had utilitized ball reservoirs there surely would have been mention, again and again, of such balls, of charging up such balls, and since ball reservoir guns, with their limited air storage, virtually require spare balls, there would have been mention of having extra reservoir balls, or of replacing reservoir balls.

The most conclusive consideration that the Lewis airgun could not have had a ball reservoir comes from that observation that the airgun could fire 40 times on a single load. Brass and copper ball reservoirs, even those made by the finest craftsmen of the period, would have been very limited in their pressure limits and thus their capacity of stored air. Gaylord (personal communication, 25 May 1999) stated that a typical airgun ball reservoir would be capable of safely holding only enough air for perhaps 10 to 12 shots, certainly not more than a few more than that. It has variously been reported that a heavily charged butt reservoir gun could fire about 40 shots, although the last score or so of those probably would be of very limited power. Thus the Lewis air rifle must have had a good sized butt reservoir.

Captain Lewis reported replacing the sights on his air rifle after they had been removed by an accident. Surely he would have secured them especially well, perhaps by firming down the edges of the sight retaining dovetail slots, after their accidental removal. Thus we should look for a rifle with both a front and a rear sight, well secured.

Captain Lewis recorded great detail on his supplies and equipment. He reported that he approached Schuylkill Arsenal at Philadelphia for his special hardware needs but that they were not able to help him and so he had firearm rifles prepared for him at Harpers Ferry Armory about 150 miles west. Certainly the airgun wasn’t going to be provided by Schuylkill Arsenal or Harpers Ferry Armory.

In the four months that he spent gathering equipment and supplies for the expedition Lewis constantly traversed the roads between Philadelphia, Washington, Lancaster, Harpers Ferry, and finally Pittsburgh. Frank Tait (personal communication, 1 October 2000), studying President Jefferson's biographies and Mr. Jefferson's Army, Political, and Social Reform of the Military Establishment 1801-1809 by Theodore Crackel, NYU Press (1987), has pretty clearly established a time line which indicates when Captain Lewis was in Philadelphia. There is no suggestion that he had ever visited Philadelphia prior to 1803. He must have been in Philadelphia no earlier than 9 May 1803 and was in Frederick, Maryland by 9 June 1803, not returning to Philadelphia until after the end of the expedition. Thus, with a maximum of one month in Philadelphia, he certainly did not have time to have an airgun made specifically for the expedition.

Captain Lewis must have purchased his airgun somewhere in the roughly one hundred and fifty mile wide triangle formed by Philadelphia, Washington, and Pittsburgh. I base the idea of Lewis purchasing the airgun on his remark, when writing in the expedition journal, about the airgun injuring a woman onlooker, which referred to it as the airgun “which I had purchased”. Henry Stewart felt that someone probably lent him the airgun, but it would seem that Lewis would have written such a remark only if he had recently purchased the gun. We know from Wolff (1958), and the collecting experience of myself, and other leading American airgun collectors, that only one shop, the clock/gun/instrument shop of Seneca and Isaiah Lukens in the greater Philadelphia area, is known to have produced butt- reservoir airguns during that period in that entire area. (Although the Lukens shop never developed a strong enough reputation to ever be so listed, the enormous resources of the Heer de Neue Støckel [1978] references indicate that they evidently had the Philadelphia area to themselves until Jacob [Joseph?] Kunz, an associate or seller of Lukens airguns, developed his trade to the point of being noticed - first being mentioned about 1814). Philadelphia was a small place then of only about forty one thousand persons. (About a third of the present size of the town of Santa Rosa, the "city fathers" would call it a city, near my home - a place where even today, despite the lack of the provincial feeling of 19th century towns and cities, one could find out almost immediately who in the entire area makes or repairs guns). Lewis is known to have socialized with several of the area’s leading residents, including the whole American Philosophical Society and the Peale Museum crowd. (Again, using a modern parallel, it is possible even today to meet with virtually all of the regional "movers and shakers" of the entire Santa Rosa area at a single party.) Much of this information came from my friend, the late Henry Stewart Jr., who was a long time resident of Philadelphia and who had made a long and intense study of its early leading citizens and their families. He recorded that several friends of Charles Willson Peale, the famous American portrait artist, had noted that Lewis met Peale, who was also the founder of the Peale Museum and a long-term, leading member of Lewis’ beloved American Philosophical Society. Carolyn Gilman, Special Projects Historian at the Missouri Historical Museum in St. Louis confirmed this (personal communication, May 15, 1999). Lewis was virtually compelled to meet with the area's intellectual cream while in Philadelphia because that was when he was elected to membership in that prestigious society. Isaiah Lukens was one of the founders of the Franklin Institute, Philadelphia and was elected as its first vice-president and held that office for many years. Peale was well acquainted with the Franklin Institute, having painted the portraits of many of its members. Stewart noted that Peale was a close friend of Isaiah Lukens, so it would have been almost impossible for Lewis and Lukens not to have met before the expedition. Although the Lukens shop itself evidently was in the little nearby village of Hampton at that time, most of its business, indeed its very identity, and perhaps an office or a seller (Jacob Kunz?), would have been in the prestigious gun-making area of greater Philadelphia area. And, as noted later in this treatise, the airgun barrels, even the air reservoirs, and surely the hammers, for the Lukens airguns very likely were produced or sold in Philadelphia. Note that the Lukens shop was so closely associated with Philadelphia that they marked their guns with that city's name.

Isaiah Lukens (born 1779) was the son of Seneca Lukens (born 1750/51), a clock and instrument maker. It is quite likely that Seneca had begun some work on airguns as this would have given him a market with virtually no local competition. (The combination of making clocks and airguns was common. It is interesting to note that some of the small springs in the Lukens guns actually are clockmaker's springs and that the air valve is the type of device that an instrument maker, rather than a gunsmith, would have designed.) Perhaps with input from some of the many talented and skilled Europeans pouring into the area and/or Coleman Sellers, he may have started development on a fairly simple modification of the outside lock style of butt-reservoir airguns which had been known in Europe for about two centuries. Seneca may have encouraged and trained Isaiah, and perhaps his mechanic/inventor young friend, Coleman Sellers, in this area and it is possible that he/they actually was the primary maker(s) of the Lukens DNH airgun. The existing Lukens airguns do not bear a first name or initial - though most writers have attributed them to Isaiah.

Isaiah Lukens became even more renowned than his father, Seneca Lukens, as a clock and instrument maker. Isaiah evidently was a brilliant and highly productive person. There would be little doubt that he would have learned clock and instrument, and perhaps airgun, making in his early teens and there is no reason to believe that he had not been making clocks, and airguns also, for several years before his probable meeting with Lewis when Isaiah was 23 years old. (As noted above, neither Seneca nor Isaiah Lukens appear in the records as gunmakers; apparently their apprentice/associate/seller Jacob Kunz (as marked on guns, but also spelled Kuntz or Coons) was the one to develop the trade to the point of notice.)

One of the other two Lukens .32” caliber air rifles (fig. ) that Mrs. Beeman and I examined and disassembled in the Stewart collection at Virginia Military Institute is an air rifle, in much better condition than the Lukens DNH specimen, marked “C. Sellers, No. 231 High St.., Philada”. (I will refer to this arm as the Lukens Sellers airgun.) Stewart noted that Coleman Sellers (1781-1834) was a close friend of the famed artist Charles Willson Peale (Coleman Sellers was married to, or later married, Sophonista Peale, Peale’s daughter). Carolyn Gilman, Special Projects Historian at the Missouri Historical Museum, reported that it is known (personal communication, 15 October 2000) that Peale, several of Peale’s friends, and Lukens socialized during his visit to Philadelphia. While socializing with the Peales, Lewis very likely met Coleman Sellers, and Sellers, or C. W. Peale himself, very likely would have referred to the wonderful airguns in the Lukens shop. Thus we are drawn to the idea that Lewis met Lukens, whose shop was the only air rifle shop available to Lewis in the small time/location window when he was gathering expedition equipment and supplies.

The marking of Coleman Sellers

name on the barrel of the "Sellers" airgun may be very significant.

Typically, that is the location of the barrel maker's name, while the

left lock plate is the area where the owner's name, if so marked, is

placed. Coleman and Isaiah were young men, of almost identical age, both

of whom had fathers of great mechanical ability and accomplishment.

(Coleman's father, Nathan Sellers, had been commissioned by George

Washington to make the first paper making molds in America. By

the end of the Revolutionary War Nathan had become wealthy from that

business and had branched out into other manufacturing. The Sellers family lived

at 231 High Street in Philadelphia until Nathan retired and moved to an

estate in Upper Darby in 1817. Coleman Sellers died May 7, 1834 in his

home at No. 10 North 6th Street, Philadelphia.) Martin Orro has

suggested (personal communication 14 October 2004) that is very possible

that Coleman and Isaiah, both young mechanics and inventors in the

closely-knit Philadelphia area, became friends and, as part of tinkering

with various mechanisms, developed a mutual interest in airguns. Bronze

barrels of small calibers and with high groove count rifling apparently

were not known in the Americas at that time but some were available in

Europe.. That Coleman's name appears in the finisher/maker's position on

at least one barrel (his own gun?) indicates that Coleman may have used

his father's manufacturing import connections to obtain some barrel

blanks from Europe.

Evidently the Sellers used steam engines in the family mills before the

turn of the 19th century. This would mean they possessed facilities for

maintenance, repair and limited part production of pressure tank parts.

Coleman later developed locomotive boilers. Coleman could have used this

interest and their factory facilities to copy the air reservoir from an

ordinary external lock airgun. Such buttstock shaped reservoirs and

simple valve mechanisms had been known for well over a hundred years. It would have been natural to make the

first, experimental air reservoir of this series of airguns from easy-to-work

copper. That the copper reservoir is a simpler shape than the later

Lukens air reservoirs also suggests earlier construction. Seneca Lukens' knowledge of pattern making and brass foundry techniques

would have been a natural base for his and/or Isaiah's

work on developing the receivers and other cast parts. The air valve

springs and bolts and the

firing lug springs clearly came from the clock making side of the

partnership and the locks, at least the hammers, were simply standard

flintlock units locally made or locally sold English imports. The inclusion of Coleman Sellers in the making of the Lukens

airguns is lent support by the fact that it would seem that

Coleman Sellers was too young to have been the kind of wealthy gentleman

that typically buys such expensive guns.

The smaller

caliber would make sense if a couple of young friends were making these

airguns for use in the greater Philadelphia area. There probably weren’t

too many “b’ar” around those parts by the early 1800s.

Of course, there is the possibility that Captain Lewis purchased the airgun from someone else who simply happened to own one. The fact that Lewis' airgun ended up in the Lukens shop after the trip would detract from this consideration. Because it was virtually unknown in 1847 that Lewis had carried an airgun, and that the Lewis & Clark expedition itself was poorly known then, the auctioneer had to have seen a tag saying, or been told, that item 95 in the estate auction was Captain Lewis’ airgun. The auction notice stated that the airgun had been made for the expedition. We now know that there simply wasn’t time for custom building an airgun, but the auctioneer probably assumed that because the airgun came from the Lukens shop.

While it is very possible that some items in the Lukens estate sale were not made by Lukens, it seems most unlikely that item no. 95 was added to the Lukens estate sale from non-Lukens sources. We have no reason to doubt the truth of the auction flyer and it is too much to conceive that an auctioneer, surely unfamiliar, as was almost everyone at that time, with the fact that an airgun had even been on that then little known trip 44 years earlier, would come up with such a story for this particular airgun.

The idea of a rifle which would not need powder on such an extended trip through remote areas surely would have been extremely appealing to the technically oriented Meriwether Lewis, just as it was to later American explorers, such as Pike and Long. Lewis and Clark’s report of their airgun probably was the reason for Stephen Long adding an air rifle to the armaments of his “Scientific Expedition” which left St. Louis in 1819 (Garavaglio and Worman, 1998). Other notes in this interesting web: we know of the handsome appearance of the young Isaiah Lukens from a fine portrait of him painted by C. W. Peale in 1816 (not 1860, the date which appears in the transcribed notes of Stewart’s 1982 talk - that would have been 14 years after Lukens’ death!). Peale also did fine portraits of both Lewis and Clark in 1807 or 1808, after the “Voyage of Discovery” Expedition.

If we knew the caliber of this airgun it would be a tremendous help. The original journals of Captains Lewis and Clark, as presently presented, make no mention of the airgun’s caliber. A consideration that the airgun might have been of the same caliber as the soldiers’ rifles brings us to consider the caliber of those firearms.

If Lewis had supplied his men with U.S. Model 1803 flintlock rifles, as has been the tale for decades, it would mean than these rifles probably were .54” caliber. Tait (1999a) noted that Carl P. Russell’s (Russell, 1960) flat statement that Lewis and Clark carried the 1803 model has long been treated as the final word on the subject. However, Russell gave no citations for that claim and may have been influenced by incorrect editing in the Elliot Coues edition of the Lewis and Clark journals. That has been blindly repeated (Halsey, 1984, etc.). Tait’s paper claims that Lewis was not involved in the design of the Model 1803 and that that model did not yet exist when Lewis selected 15 rifles from the Harpers Ferry Arsenal in March 1803. Tait presents an argument that the rifles obtained by Captain Lewis were U.S. Contract Rifles of 1792. Tait notes that the specifications for that rifle call for a bore firing lead balls weighing 40 to the pound (almost .49” caliber). Tait (personal communication of March 15, 2000) indicates that these rifles were indeed of .49” caliber bore, with balls running about .475” to .480”, contrary to many tales that these contract rifles varied greatly in caliber. When Captain Lewis presented his requisition for 15 flintlock rifles, he certainly would have called for, or made, careful selection of fifteen fine specimens. Ernie Cowan and Rick Fuller (display at Baltimore Arms Show, March 19-20, 2005; Keller and Cowan 2006) make an extremely strong case that Lewis' fifteen "short rifles", acquired during his Philadelphia visit in 1802, were an "Model 1800" version of the Model 1803 flintlocks. In any case these guns evidently were fitted with interchangeable locks. The concept of interchangeable parts was dear to the hearts of both Thomas Jefferson and Meriwether Lewis and, as noted by Captain Clark in his journal, such a feature was invaluable on an expedition of this nature.

Captain Clark had a personal flintlock rifle “the Size of the ball which was 100 to the pound”. That translates to .36” caliber. (Clark’s expedition notes refer to it as his “Small” rifle. Here the word "Small" very possibility was in reference to its maker. A .36” caliber flintlock rifle marked “Jn. Small, Vincennes”, which the Clark family originally claimed was carried by Captain Clark on the expedition, is in the Missouri Historical Society Museum. Støckel (1978-82) records John Small as a gun maker and sheriff in Vincennes, Knox County, Indiana during the period 1780 to 1823. Bud Clark, a modern descendent and long time student of the Lewis and Clark expedition, reported (personal communication, April 15, 2002) that the family now knows that the displayed gun was produced after the expedition.

Apparently only a single lead ball has been found in archeological examinations of the expedition’s campsites. Jay Rasmussen’s excellent website (www.lcarchive.org/fcexcav.html) about the archaeological excavations at Fort Clatsop near Astoria, Oregon reports that Ken Karsmizki found a lead object during the 1997 excavations of that expedition camp site. It seems to be a lead gun ball flattened on one side, perhaps from being fired against a hard surface. The weight of 4.2 grams would indicate a caliber of about .36” - in line with the bore size of Clark’s Small flintlock rifle, mentioned above. Karsmizki reported (personal communication) that there apparently was no rifling mark, indicating that it may have been fired with a patch. Isotopic analysis of the lead pointed to the Buick mine in Missouri - which is consistent as a possible supply point for lead taken on the expedition.

Considering that lead for gun balls would be an extremely precious commodity on a trip of such duration and nature, it is understandable that lead balls would be husbanded even more carefully than money back home and not lost around campsites. If any balls were lost, it is even less likely that they would have been ones from this one airgun which Lewis seems to have carefully maintained as his own. We must note that archeological examination of the expedition’s campsites has been extremely limited to date.

It would be delightful if we could substantiate a rumor started (as per personal communication with National Rifle Association - confidential source) by the Smithsonian Institute, that the airgun was the same caliber as the soldiers’ rifles. However, even that would not now define a specific caliber and, in any case, could be a mistaken assumption of an early writer not closely involved with the airgun. On the basis of previous information, Captain Lewis’ airgun could have been of almost any caliber capable of hunting and impressing the Indians. In other words, it must have been at least .32” caliber.

Tait (personal communication, 1 October 2000) and I independently realized that the recorded ability of Captain Lewis' air rifle to fire 40 times on a single charging surely is a clue to its caliber. Gary Barnes, today's leading authority on big bore air rifles, determined that a modern compressed air gun, of .45" caliber, with a 9.42 cu. in. reservoir could fire eight shots at about 120 ft. lbs. of energy. Calculating from those figures, a .45" caliber air rifle with a 30.9 cu. in. reservoir, such as the Lukens DNH air rifle, would be able to fire perhaps 40 or more total shots. Larger bore airguns would be capable of fewer shots per charge.

One clue, or factor, that has been overlooked, or just quietly assumed by those associated by those close to the quest for the Lewis air rifle, was the rarity of airguns in America around the start of the nineteenth century. It would be nice to identify some of actual firearms carried on the Lewis and Clark expedition, but whether we accept Tait’s claim that the soldiers of that expedition were using Model 1792 Contract rifles, or the more recent, and now more widely accepted, claim by Keller and Cowan (2006) that they carried special versions ("Model 1800") of the U.S. Model 1803 rifles, those specimens would have come from series which contained thousands of similar guns. On the other hand, large bore airguns have always been uncommon and the overwhelming majority of those that had been made by the beginning of the nineteenth century were still in Europe. Such airguns must have been not just scarce, but extremely rare, in the areas frequented by Meriwether Lewis around 1800. It is clear that rather than having to pick one specimen from thousands of similar military or factory production guns, that when it comes to determining the Lewis and Clark airgun, we probably have to pick from only a handful of possible specimens, maybe from only one or two guns which would have been appropriate and available in the small time and space window.

We do know that a large portion of the specimens of expensive large bore airguns, did survive through the ages. So, not only does the Lewis and Clark airgun probably still exist, but also it should be possible to narrow the candidates down to a precious few.

As noted earlier, we know of only one American shop making butt reservoir airguns prior to the Lewis and Clark Expedition. That was the shop of Seneca and Isaiah Lukens in the Philadelphia area. Isaiah Lukens (born 1779) mainly was known as a clockmaker from the late 1790s until his death in 1846. He made many of Philadelphia’s large clocks, but he is best known for building the big public clock that was installed on Independence Hall, in Philadelphia, in 1828. He spent the period from 1828 to 1840 in Europe. Apparently airgun production of the Lukens shop was very limited. The main work was clocks and the airgun production, especially the later airgun production, apparently was mainly air canes. We really don't know the full span of Kunz’s airgun work. Jacob Kunz (born 1780) was first mentioned in the literature (Støckel, 1978) as a gunsmith in the Philadelphia area from 1814 to 1855. However, he may have been a gun maker, designer, or at least, seller in 1803 when Captain Lewis was in the Philadelphia area and may have been at least partially responsible for the Lukens interest in airguns and even some features of the Lukens designs.

Fig. 4 Isaiah

Lukens, courtesy of Library of Congress

Click on picture for larger view

It is possible that Seneca and Isaiah Lukens, who, so far as I can yet determine, are unknown in the gunsmithing records, had Kunz make air rifles for them and mark their lockplates with the Lukens name. More likely, it was the other way around, with the Lukens men making airguns under their own name and later under the Kunz mark. The "birdcage" design of Lukens' air valve mechanism is the kind of thing that a clock/instrument maker would have added to the modified external lock airguns. However, I think that Seneca or Isaiah Lukens and possibly Coleman Sellers, at least designed, and probably made, at least two, and probably all, of the four air rifles, which are known to the author, that bear that name. Kunz may have obtained guns from Lukens, but probably later made some of the rifles which bear his name as he became more skilled and finally became a 19th century American gunsmith worthy of historical note. Kunz seems to also have taken on the Lukens air cane designs and greatly improved them, even adding a breech loading mechanism. The air rifles marked Kunz and Lukens very closely follow similar designs, but later Kunz airguns show a very interesting evolution to a completely enclosed lock mechanism and a two shot air/percussion capacity.

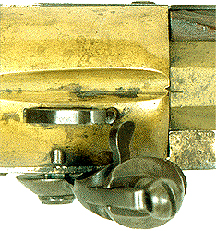

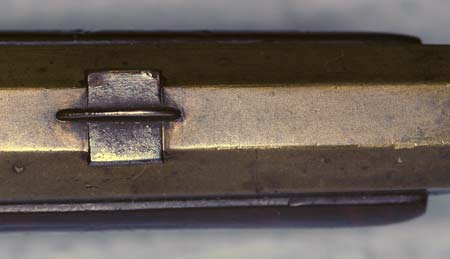

At this time, apparently only sixteen air rifles from the Lukens and Kunz shops are known, five are marked Lukens, eight are marked Kunz, and two are unmarked. The basic pattern of these is Kentucky style with full-length wood forearms and handsome Kentucky style trigger guards. I have examined all eight of these air rifles in the Henry Stewart collection at VMI. Two of the others, one marked Lukens, and one unmarked, but reasonably ascribed to Lukens, are in the Buffalo Bill Cody Firearms Museum. Another specimen, reportedly .31" caliber, here known as the "Copper Lukens"*, was sold from an illustrated color ad in the March 1989 issue of Man At Arms; the author does not know of its present location*. Two of the Kunz air rifles, a Lukens air rifle, and an unmarked one probably by Kunz, are in private collections, the identity of which I cannot disclose at this time. Three of the VMI museum rifles are shown in figure . They are very similar, built around an extremely ingenious, unique lock mechanism. Gooseneck and double neck hammers had been known on air rifles for a long time, but their function primarily was just cosmetic or to be used as cocking handles. However, the Lukens/Kunz school of airguns was quite different. That is, unique among all air rifles known from other makers, the early Lukens/Kunz air rifles simply use a regular flintlock hammer in which is clamped a very special metal lug instead of a piece of flint. This firing lug (figs. ) is fitted around the hammer’s jaw clamping screw. When the gun is cocked, the lug projects at a right angle inward from the hammer. Upon pulling of the gun’s trigger, the hammer carries the projecting lug forward, striking an air release lever that projects from the rifle’s receiver. While the forward moving lug engages this lever, the lever transmits its motion through a linkage rod (figs. ), which in turn pushes the striker rod against the air reservoir’s valve stem. This opens an internal air release valve and releases the blast of air that propels the projectile out of the bore. As the hammer moves towards its forward, resting position, the lug overrides the rear surface of the air release lever and the spring loaded air release valve is allowed to snap shut, stopping the flow of compressed air. The air valve is held open as long as the firing lug is riding over the air release lever. Such a timed arrangement is superior to simple knock-open valves in that the air release valve can be held open longer and thus the gun can release more air per shot and have greater power and consistency (in such airguns the projectile typically has not left the muzzle before the release of compressed air has ceased). When the hammer is recocked, the forward edge of the air release lever forces the firing lug to pivot out of its way into the jaws of the hammer. This position of the lug could serve as a simple safety. The lug must be pivoted out to the side to again make it ready to impact the air release lever during the next shot. This action probably was provided by a small return spring, but could be accomplished manually in the absence of such a spring. Notches (fig. ) in the firing lug serve to hold the lug in the proper positions and to engage the proposed return spring. After the striker swivels to bypass the air release lever during cocking, the return spring would push the striker back into its ready position. Although none of the VMI specimens still have this return spring, VMI Museum Director Colonel Gibson examined (personal communication, 20 February 2001) such a spring on a similar Lukens air rifle at the Buffalo Bill Cody Museum. He reports that the return spring is an approximately 180 degree section of a flat circular spring -- a clockmaker's spring!

*Side note: Features of the "Copper Lukens" air rifle: see Arms and the Man magazine, pg. 9, March 89. Full length Kentucky style stock rifle, similar to DNH in appearance, but, as expected of a fine gentleman's gun - this specimen is in excellent condition. Silver trigger guard of same style as DNH gun, .31 cal., 15 groove octagonal barrel, 34 5/8” long. Three silver pipes around ramrod. Silver foresight with blunt side back. Lukens name in big block letters on plain lock plate. Gooseneck flintlock hammer. "Brass" receiver with silver lined sight groove. Bare copper buttstock shaped air reservoir. Full length Kentucky style stock. From Joe Kindig collection. Information on this specimen, even confidentially supplied, is actively solicited by the author at Box 516, Healdsburg, CA 95448, or website@Beemans.net by email. Such information is needed to better understand the Lukens airguns and would add value to the specimen.

Fig. 5. Above

Top: Kunz .32" air rifle (VMI museum no. 88.031.009). Middle: Lukens DNH

air rifle. Note air release lug in fired position (VMI museum no.

88.031.007). Bottom: Lukens Sellers air rifle (VMI number 88.031.008).

Note the sighting grooves cast into the two Lukens receivers and, in the

lower image, the engraving chased around the sighting groove of the

Sellers gun. Cast-in sighting grooves are a fairly common feature of

muzzle-loading rifles of this period. Photo/R. Beeman.

©2001

Robert David Beeman.

(Click on image for larger view)

Stewart (1977) notes that the basic arrangement of striker/valve release described above is similar to the airgun lock mechanism of the Utrecht school, circa 1650 (the "external lock airguns" known to some airgunners today as the Liege lock mechanism) (Wolff, 1958, figs. 41-44), where an outside overhead striker was developed around an external cocking lever. Several of the external lock airguns in the Beeman collection also show an air release lever which is rather similar to that of the Lukens airguns where that lever is more central and partially enclosed by the receiver - a natural evolution. The Lukens airguns clearly are an extension of such butt-reservoir, external lock airguns. However the Lukens design adds a very special, delightfully simple, feature by using a regular flintlock hammer with a specially keyed, swinging striker lug. Although Lukens used regular production flintlock cocks or hammers, his locks differ from a true flintlock in that there is no frizzen or powder pan and, of course, no flint. I think that we should classify this mechanism as a special variation of the outside lock airguns. It is a very clever, simple, well built arrangement, and as noted by Stewart, it is absolutely unique to the Lukens/Kunz school of airgun design. Later air rifles of this series, made by Kunz, evolved from the flintlock hammer to what appear to be modified percussion hammers.

Fig. 5. Lukens DNH air rifle. Right rear view of double neck (post) hammer. Note the firing lug clamped in the hammer's jaws. This is the fired position. Careful examination will show the exposed end of the firing lug that has released and passed over the air release lever projecting from the top of the receiver. Photo/Tom Gaylord.

Fig. 6 Kunz .32" caliber air rifle. Showing inner side of gooseneck hammer and firing lug after it has released and then passed over the firing lever which projects from near the midline of the receiver. This is the mechanism that is unique to the 1800s Philadelphia Lukens/Kunz school of airgun design. Note absence of a sighting groove on the receiver. The indentation along the rear of the center fusion line reveals that the receivers of the Lukens/Kunz airguns are too thin to allow milling of sighting grooves - they must be cast in. Photo/Tom Gaylord.

Fig. 7.Lukens DNH air rifle. Top view showing hammer with firing lug after it has passed over the air release lever which is just to the right of the midline of the receiver. Note the almost perfectly aligned witness marks on the barrel and receiver indicating an excellent match of barrel and receiver. Photo/R. Beeman, ©2001 Robert David Beeman.

Note developing crack in the Lukens Sellers

gooseneck hammer.

Figs. 8 - 11. Four views of the Lukens Sellers air rifle.

The underside view shows the handsome cast brass trigger guard, keyed into the

receiver halves at the back and secured by two screws in front. The Lukens DNH rifle also has

this styling. VMI photos.

Click on blue border images for slightly larger views.

A gooseneck hammer (fig. ) seems to be basic to the Lukens/Kunz Kentucky style air rifles. The Lukens Sellers airgun has a gooseneck type of hammer (which shows a fracture line across it). Four other air rifles ascribed to Lukens, but outside the VMI museum, have gooseneck hammers. Four other “Kentucky style” air rifles, the lockplates of which are marked Kunz, have an identical type of firing mechanism and both have the gooseneck type of hammer. Thus, it is most puzzling to see the rounded double neck, military style hammer on just one Lukens air rifle.

Fig. 12 Lukens DNH air rifle. Right outside view of lock with "flint" clamp removed. Photo/R. Beeman, ©2001 Robert David Beeman..

Fig.13. Lukens DNH air rifle. Inside view of lock mechanism showing removed flint clamping plate (inside view - note pits into the metal to improve the grip on the flint or firing lug), firing lug, and clamping screw. Note especially the bright finish on the mainspring which appears to be a replacement. The clockmaker style firing lug return spring, typically found in Lukens/Kunz airguns and prone to "escape", is missing. Note also that the Lukens name is also stamped on the inside of the lock plate. Photo/R. Beeman.©2001 Robert David Beeman.

The Lukens air rifle with the double neck hammer is conspicuously marked Lukens in large engraved script, both inside and outside of the lock plate. The only other markings easily evident on this gun are the letters “Phild-a.” on the left side of the receiver (fig. 3) and a ring of encircled dots which surround the muzzle opening (fig. ). The other Lukens air rifle, noted earlier, is marked with C. Seller’s name and his early Philadelphia address on top of the barrel and Lukens on the lock plate.

Fig. 14. Muzzle of Lukens DNH

air rifle showing circled dot markings and land and groove rifling. Photo by

Tom Gaylord

(click on

image for larger view)

Of the three Lukens/Kunz air rifles examined closely, we found all three to have receivers different in size, features, and proportions. All show clear evidence of careful, integrated design and skilled assembly. They have three different combinations of lock plate attachments. There is absolutely no indication that these airguns, or any of those of the series which followed them, were improvised from previously existing guns. Careful examination of the photos (figs. ) will show these features. All three had a forward securement screw. The Lukens DNH rifle had a rear flange that fitted under the edge of the receiver. The Lukens Sellers rifle has no flange, but has a screw near the middle of the lock, which secures the plate to the receiver. The Kunz .32” caliber air rifle has a rear flange and both a middle and forward securement screw. This would appear to be an evolutionary series: the Lukens DNH gun has the loosest, least secure arrangement of the examined guns. I have not been able to examine this arrangement on the Copper Lukens. The Lukens Sellers rifle substitutes a middle screw for the rear flange and thus allows the plate to be securely screwed down. The Kunz rifle has all three, a rear flange for securement and to facilitate alignment of the plate when securing it, plus a solid middle and forward screw for very secure attachment of the lock plate. It is my conclusion that the Lukens DNH rifle is the oldest of these three and that the Kunz rifle is the most highly evolved; the most recent production of the series. It is very probable that these particular Kunz rifles were made after Lewis departed on the expedition in 1803. The Lukens DNH rifle seems to have been one of at least two Lukens air rifles that existed in time to be the airgun available to Captain Lewis for his “Voyage of Discovery” across America. Almost surely, one of those, the "Copper Lukens" air rifle, not yet examined, is the first of the known specimens of Lukens air rifles.

Fig. 15. Lukens Sellers air rifle. External view of complete lock mechanism. Note gooseneck hammer with firing lug inside the jaws of the flint clamp. Photo by R. Beeman, ©2001 Robert David Beeman.

Fig.16 Lukens Sellers air rifle. Internal view of complete lock mechanism. Note the squarish, "clockmaker's" style mainspring. Photo/R. Beeman.©2001 Robert David Beeman.

Fig. 17. Kunz .32" caliber air rifle. External view of lock mechanism with firing lug removed. Note gooseneck hammer and stop spurs on the firing lug. Photo/R. Beeman.©2001 Robert David Beeman.

Fig. 18. Kunz .32" caliber air rifle. Internal view of lock mechanism with firing lug removed. Photo/R.Beeman, ©2001 Robert David Beeman.

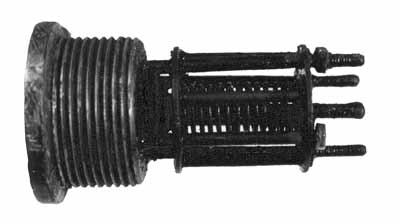

Fig. 19 -20. The "sliding birdcage" valve assembly of the Lukens DNH airgun reservoir is a complex appearing device to do the critical job of sealing in the stored air. Actually, this is a simple variation of the basic air valve design found in most butt reservoir airguns of the previous century or two (and in the various, very different, valve units of the Girandoni-type airguns where a central, non-adjustable valve shaft was contained within a central coil spring and housed in a tubular or conical outer housing). The Lukens valve seems to have been made up from the type of plates, bolts, and springs that would be common in a clock-maker's shop. The "birdcage" assembly simplified construction by avoiding the need to cast a valve housing. This simple modification also represents a one step improvement in that it provided adjustability of valve compression, preload and travel while the basic airgun valve system is not adjustable. Note in the lower view of the removed valve assembly that one of the four support shafts appears to be broken off at the nut. Photo/R. Beeman, ©2001 Robert David Beeman.

Fig. 21. Lukens DNH air rifle. Top view of the air reservoir showing the forward tip of the stem of the intake/exhaust valve. The pin shown in the center of the figure below pushes back on this stem to cause a momentary burst of air for firing. The valve seat, around the pin, probably was made of horn or "jacked" leather. Such air reservoirs, of buttstock, conical, and semi-conical shape had been common for at least a century or two. This buttstock reservoir seems to show advancement over a previous Lukens reservoir (in the "Copper Lukens") by adding a cheek comb along its top edge. Photo courtesy of VMI.

Fig. 22. Lukens DNH air rifle. Detail of receiver end of valve assembly, showing valve stem. This unit screws to the butt reservoir via the female threads seen in the image to the left. Photo by Tom Gaylord.

The dating of the double neck hammer (figs. ) on the Lukens DNH airgun must be considered. A flintlock rifle hammer was just too large for the role; a pistol hammer would have been ideal. Stewart and Harrison felt that the double neck hammer on this gun was from a U.S. Model 1836 flintlock military pistol and thus that this hammer must have been added after 1836. This evidently was the primary reason why Stewart had definite doubts that the Lukens DNH airgun really was the Lewis and Clark airgun. Double neck hammers of this rounded type are found on American, and even French, flintlock firearms which were built prior to 1800.

Fig. 23. Double Neck Hammer of the Lukens DNH air rifle. (Height of the main hammer piece is 1.582": upper flint clamping plate is 0.695" by 1.033"; total length of screw is 1.305"). Note that upper flint clamping plate is shorter than the lower plate. Photo/Virginia Military Institute.

What could have been the source of the replaced DNH hammer? Colonel Gibson, the VMI Museum Director, noted (personal communication, 16 October 2000) notes that French gun parts would have been available from French trade with the Native Americans who already had flintlock firearms or they could have been obtained in the region's predominately French towns. A likely source candidate is the French Model 1777 flintlock pistol. Perhaps an even a better candidate is the U.S. Model 1799 North and Cheney (Berlin) flintlock pistol. This large "horse pistol", the really first official U.S. pistol, was modeled on that French M1777 pistol. Garavaglia and Worman (1998) and Frank Tait both note that there were a large number of M1799 North & Cheney pistols available in the appropriate time window, at least at the Schuylkill Arsenal in Philadelphia.

Fig. 24. U.S. Model 1836 Military

Flintlock Pistol.

After

Garavaglia and

Worman (1998)

Fig. 25. French Model 1777 Military

Flintlock Pistol

After

Moore (1967)

Could a M1777 or M1799 pistol, or a replacement part in the spare parts inventory, have supplied the replacement hammer on the Lukens airgun? The replaced double neck hammer ("double throated cock") on the Lukens air rifle seems to match the proportions of the North and Cheney flintlock pistol quite well but not match the proportions of the M1836 hammer in the specimen shown by Garavaglia and Worman (1998). Comparing rough measurements of the height of the hammer from its base to the top surface of the lower jaw to the width of the hammer base : North & Cheney height = 190 %, Lukens DNH = 180 %; N&C width = 84%, Lukens DNH = 79%. The height is 223% of the width for both guns! The M1836 hammer has a much broader base, with a width to height ratio of 2.09.

The head of the hammer pivot screws on both the Lukens DNH rifle and the N&C pistol are much smaller than the head of this screw on the M1836. The head of the hammer pivot screw of the N&C pistol is about 57% of the hammer's width; the screw head on the Lukens DNH gun is about 50% of the hammer's width. The same screw head on the M1836 is only about 36% of the hammer's width. An imaginary line down the back of the lower member of the N&C and Lukens DNH hammers is almost in line with the rearmost curve of the hammer's base, while in the M1836 the rear curvature of the base projects well behind such a line.

Thus, while the hammer of the Lukens DNH air rifle differs significantly from that of a U.S. Model 1836 hammer, some hammers of the Model 1799 North & Cheney and Lukens DNH hammers seem to be similar enough that they might have been interchanged, with some fitting, to operate on either gun. However, the hammers of some North and Cheney pistols have quite different shaping. Ernie Cowan (personal communication, 20 November 2004) feels that the hammer on the Lukens DNH rifle better matches that of the Waters and Johnson flintlock pistol of 1836.

Click on pic for larger image

Fig. 26. M1799 North & Cheney Pistol -

from Reilly (1986)

A difference from the M1779 hammer, in this very limited comparison, appears to be the presence of a concave area in the Lukens DNH hammer around the opening into which the clamping screw protrudes. Such a concave area does not appear on the hammer of the M1799 North and Cheney pistol illustrated by Garavaglia and Worman (1998). The original French M1777 pistol, from which the M1799 North and Cheney pistol was copied, as illustrated by Moore (1967), shows exactly the same concave area as the Lukens DNH rifle’s hammer. The cock/hammer of the North and Cheney pistol illustrated by Reilly (1986) does show a concave area like the Lukens DNH hammer it and appears to be almost identical to the DNH hammer. Other flintlock pistols by North had such a concave area in DNH models by 1816 at the latest. It seems probable that such a concave area also was present in at least some earlier guns made by North. Tait points out that in that period, gun locks, including the hammers, were made by independent filers, not by the gunsmiths. Different independent workers would be expected to make slightly different sizes, sometimes appearing quite different in cosmetic features but similar in style and proportions. The actual differences in gross outside dimensions and cosmetics could be due to differences in hand trimming and finishing, even if the rough blanks had been the same and there is no assurance of that. (Garavaglia & Worman (1998) report that the first U.S. governmental contract to require lock parts to be interchangeable was for the U.S. Model 1813 pistol.)

At this time it apparently is not known just what type of locks were on the fifteen firearm rifles that Lewis obtained from Harpers Ferry Arsenal when he arrived there in mid-March 1803. Tait (1999) ended his paper on the U.S. Contract Rifles of 1792, by lamenting that we still don’t know what kind of locks were present on those firearms. Captain Lewis may have ordered his firearm rifles to be modified for his group. There is no doubt that the double neck style of hammer is more durable than the gooseneck style hammer. Tait (1999) illustrates double neck hammers, without comment on the design, on 1805 Harper Ferry rifles, confirming that that style was present in that period. The journals indicate that Lewis ordered new locks to be made to fit his rifles and the journal entries indicate that these locks and, and their parts, were basically interchangeable.

It seems quite clear that the hammer that was standard in the Lukens/Kunz design was a flintlock gooseneck hammer that holds a specially keyed and pivoting striker lug instead of a flint. It is significant that it is presently observable that a previously installed, probably gooseneck, hammer had already left its mark on the top edge of the lock plate of the Lukens double neck hammer air rifle. The double neck hammer on this gun clearly is a replacement. The most likely situation is that such a replacement would have been the result of a quite skilful, repair. The fitting of both a different style hammer and a new mainspring calls for some careful metalsmithing. Given a bellows, a simple drill, some files, and steel stock, a practiced and clever craftsman can make even rather sophisticated flatsprings - and could adapt a different hammer. (It is generally impossible to repair and retemper a mainspring. "Repairing" a mainspring means completely replacing it.)

Only someone with the original gooseneck hammer and firing lug in hand, could have fashioned this hammer replacement. If the firing lug of the Lukens DNH airgun is not one made by Lukens, it is an exact copy. It may be the original lug, salvaged from the original hammer.

There is another little noticed feature of the lock mechanism on the Lukens DNH air rifle. That is, the head of the forward lock plate securement screw of the left lock plate (fig. 2) is broken so badly that it is difficult to remove. This flaw would be very conspicuous to any gunsmith. How could it have become broken? Only someone trying to remove the lockplate could have broken it. One likely scenario would be that it was broken when someone removed the lockplate to replace a broken mainspring. While Shields had all the simple equipment that would have been necessary to replace the mainspring, or even the hammer, it would have been very unlikely that the expedition’s equipment included the tools necessary to make a new screw and it is just as unlikely that their spare parts would have included a screw of the exact configuration and thread to match that particular “civilian” screw originally used by Lukens. Shield’s only choice would have been to secure the lockplate with the broken head screw when he finished his lock repairs. However, this screw could have been broken anytime in the 19th or 20th century.

All of the known Lukens/Kunz air rifles have riflestock-shaped butt reservoirs of apparently very similar construction (fig. ). Colonel Gibson and I have closely examined only the reservoir of the Lukens double neck hammer air rifle. The reservoir has an internal volume of 590 cc, of which 83 cc is displaced by the valve mechanism. Thus the net air capacity is 507 cc (=30.9 cu. in.). The reservoir is made of two overlapping iron plates. The main body of the reservoir consists of a single piece of metal that has been bent and hammered into the shape of a buttstock. This metal sheet is overlapped and welded to form a seam about one inch below the crest of the comb on the right side. The second plate of metal is welded into the rear of the larger, somewhat oval shaped tube formed by the first piece forms the buttplate section. There may be rivets concealed within the welds, but I do not think so. There is an internal baffle, quite difficult to see in the interior of the reservoir, which is darkened by a complete inside coating of what appears to be old dried grease. (A lining of grease in such guns served to trap small debris and dirt that may be introduced into the reservoir during pumping - thus increasing the dependability of the valve.) This baffle serves a cross brace, between the inside sides of the reservoir, and could significantly increase the amount of air pressure that this vessel could hold. Extensive signs of brazing are also present - perhaps to secure the cross braces and/or as suggested by Wolff (1958), to plug holes left after the welding. This butt reservoir has such an unattractive rough and irregularly colored surface that it is very possible that it originally was covered with leather, although the air rifle made by Lukens for Sellers, and one of the Kunz air rifles, have their buttstock reservoirs finished in black enamel. The reservoir of the Lukens air rifle of the Man At Arms advertisement, the "Copper Lukens", is unusual in being made of copper. It may have been an even earlier product of the Lukens shop and probably was capable of holding less pressure than the iron reservoirs. Such a version would have been considerably less powerful and not very desirable for expedition use.

The threads of the buttstock air reservoir of the Lukens DNH airgun are especially interesting. The noted airgun maker, Gary Barnes, was kind enough to examine them for me when the Lukens’ DNH airgun was brought to the 1999 Roanoke airgun show by Colonel Keith Gibson and George Whiting of the Virginia Military Institute. The male threads of the receiver to the female threads of the valve body (figs. 8-9) are 12 TPI with a 60° pitch. The male threads on the valve to the female threads in the butt reservoir (figs. 7, 10) are close to, but not exactly, 16 TPI and close to, but not exactly, a 45° pitch. The especially interesting part is that Gary thinks that the valve-to-butt threads were cut on a different machine than the receiver-to-valve threads. He noted that even on his modern lathe it would be wasteful to cut such different threads. The set-up time would have been too great. All of the cutting tools would have to be ground on a different angle and all the lathe gears would have to be changed. A machinist usually establishes a thread pattern and uses it consistently. Thus, at least two lathes, perhaps in two different shops, were used. This suggests that the air reservoir was purchased from an outside supplier - further easing the work and design efforts in the Lukens shop. The odd-sized threads may have been a proprietary size that the maker had established, not true to any English measurement.

The receivers (figs. ) of the Lukens and Kunz air rifles are brass or bronze. Originally, Henry Stewart and I felt that the shape and style of these receivers appeared similar to receivers on “Girandoni-style”, Austrian butt-reservoir air rifles. However, such styling was known in Europe by 1750, or even well before, so it is possible that this superficial styling could have found its way to America by the end of the 1700s. The butt reservoir construction, with conical, semi-conical, and buttstock shapes, was, of course, known for at least the prior two centuries. Close examination of specimens of Girandoni and Girandoni-style air rifles in the Beeman collection reveals that while there is superficial external similarity due to being rounded, as is so common, and having the air reservoir connection, barrel base, and lock in similar locations, as would be dictated by function, the receivers of the two lines of airguns really are extremely different. The Lukens receivers consist of a pair of vertically fused metal castings, each cast (probably by rammed sand casting) from side to side, which enclose the lock and associated parts, both top and bottom. The air transfer tube appears to have been brazed in place when the receiver shells were joined. The Girandoni locks and associated parts are covered by a single piece metal receiver which is solid only on the top of the receiver; the areas under the locks are covered by the trigger guard and parts of the wooden forearm. The air reservoirs are similar only in position and function. Internally the Girandoni airguns and the Lukens airguns are completely different in design, each following designs known for over a century. There appears to be not the slightest indication that the features of one was influenced by the features of the other.

The mainspring (fig. ) in the Lukens airgun which bears the name of Coleman Sellers on the barrel appears less sophisticated than the Kunz .32” caliber air rifle’s mainspring (fig. ). The Lukens’ Sellers mainspring has square, unfinished edges, is less tapered, and has longitudinal draw file marks. It gives the impression of being the kind of spring that an early clockmaker, rather than an experienced gunsmith, would make. Kunz, as he shifted from being the Philadelphia agent for the Lukens shop to being a sophisticated gunsmith well recognized for both firearms and airguns, may have been the one to bring more refined gunsmith skills to the Lukens shop. The Kunz mainspring, certainly more recent and more refined, is more graceful with beveled edges and a more finely finished surface. The mainspring in the Lukens DNH air rifle indeed seems to be a replacement (fig. ). It has a bright blue temper and is beautifully tapered with nicely beveled edges. This mainspring looks virtually new and shows no surface rust, as if it had been made shortly before the gun was retired from active use or perhaps later.

The barrel on the Lukens DNH air rifle is brass, or perhaps ordnance bronze, 32" long, and rifled with 15 (not 17 as noted by Wolff, 1958) shallow rifling grooves. At the muzzle the rifling appears scalloped due to finishing with a very small round file. Each groove is tapered out and given a rounded bottom. This tapering would facilitate loading and reduce accuracy problems due to muzzle impacts. Within the bore the rifling lands have broadly angular shoulders sloping into the grooves. The rifling has a very long right hand twist: one turn in 40 inches and the bore is .31" caliber. Stewart (1982) indicated that such a gun would use an unpatched ball. The many, shallow rifling grooves evidently would have rendered a patch, or hard ramming, unnecessary. (For comparison: The Kunz .32" caliber air rifle had even shallower rifling grooves, also with a long right hand twist, one turn in 46 3/4 inches. As noted earlier, the muzzle of the Lukens DNH air rifle bears a ring of circled dots (fig. ), simple, whimsical decorations which enhance the airgun's similarity to contemporary, powder-burning, Kentucky rifles.

The pump for the Lukens double neck hammer air rifle is missing. However, considering the similarity of the known Lukens/Kunz air rifles we can certainly expect that the pump for one of these air rifles very probably would be very similar to the pump for another of them. We are extremely fortunate to find that the one of the Kunz air rifles is cased with an air pump (figs. ) and a pump is known for one of the unrecorded Lukens air rifles.. These pumps are unusual; the design may be truly unique among all other known airgun pumps, in that they are provided with a tapered, coarsely threaded auger screw at the end which is to be restrained during the pumping. To use such a pump, the shooter could screw it into a tree, a wooden floor, a door jamb, a barn wall, or any similar surface, and then apply the pumping strokes - even at convenient shoulder height. It is only right to suspect that these pumps probably have very similar specifications to the pump for Lukens’ DNH air rifle. And, it is possible that the missing pump for the DNH air rifle had such an auger screw. However, convenient trees would have been expected through only some parts of the trip. The pump for this Kunz air rifle is 22.63” overall, with a cylinder 19.50” long and with an outside diameter of 0.82”. The pump’s piston head (fig. ) is 0.75” in diameter and 2.50” in length and consists of a stack of washers, apparently made of oiled leather, compressed against a steel end piece honed to an almost identical diameter.

Fig. 27. Kunz air rifle pump. This pump was found cased with a Kunz combination percussion/air rifle, VMI museum no. 88.031.012. The buttstock air reservoir would be screwed onto the threaded end of the pump. A coarse threaded auger screw with finger flanges, fitted to the end of this pump, allowed the shooter to anchor the air pump to a tree or a post, The whole unit of connected pump and reservoir would be pumped up and down many times to build up a full charge of air. . The pumps that accompanied Lukens guns may have also have had an auger screw but more likely were fitted with a T handle.

Lower image shows the piston head of the Kunz air pump consisting of stacked leather washers behind a tightly-lapped steel head that originally probably had a leather tip Photo/ Virginia Military Institute.